Now It Can Be Told

SABRES USED TANKERS FOR KOREA DEPLOYMENT

by Col. Bruce Hinton

Dover AFB, Delaware, 0700, 9 November

1950: With a frontal passage nearing - rain, low ceilings, and gusty winds

- there'd be no flying today for my squadron. It looked like a pretty quiet

day. But that all changed when an unexpected phone call from 4th Group Headquarters

announced a squadron commanders meeting not later than 1100 hours. Fourth

Group (and Wing) Headquarters, along with the 334th Squadron, were located

at Newcastle County Airport, Delaware. My Squadron, the 336th, was at Dover

(not a big airlift base in those days, just me fighter squadron), with the

335th at Andrews AFB, Maryland- Quick calls to Capt. Howard 'Mac' Lane, squadron

adjutant; and Capt. Morris 'Mo' Pitts, squadron material officer, notified

them that we'd be driving to the meeting at about 0930.

It'd been slightly over four months since the 4th was deployed from its home

at Langley AFB, Virginia, to these three bases, forming a defensive ring around

Washington, D.C.. The outbreak of the Korean War had raised questions about

the security of our nation's capitol. Dover AFB was in a 'stand-by' basis

with leaky buildings. But it had a good runway and a base hospital, which

was maintained to support annual Air Guard encaropments. As 336th FIS commander,

I became the base commander.

Wing Headquarters at Newcastle was in a frenzy when we arrived. We quickly surmised that the biggest thing in our lifetime was about to happen. And so it was. The entire wing was moving overseas. Destination - Japan! All personnel, equipment, and records were to be readied for shipment. Our F-86A aircraft were to be prepared for flight to the West Coast. Many of our older Sabres would be replaced by later production models before our departure. Most of these were delivered in Newcastle, Dover, and Andrews by other F-86 Wings, principally the 56th at Selfridge and the 33rd at Otis. As it turned out, at least six replacements were flown direct to our ports of embarkation (POE) by the lst Wing at March AFB, California.

Each squadron had to have all of its Sabres airborne before 1100 hours, 11 November. The 334th and 335th would Proceed to North Island NAS, California, for shipment by aircraft carrier. The 336th would go to McClellan AFB, California, where in aircraft would be prepared for shipment, then sent down-river to Oakland/San Francisco for deck-loading onto oil tankers

Getting equipment ready for overseas deployment, selecting airmen and officers for specific tasks, receiving six replacement aircraft, and getting the whole outfit ready to leave in less than 48 hours was an assignment of Herculean proportions.

Choosing pilots was critically important, became there had been an influx of recent flying school graduates. To make matters worse, two veteran captains could not be included for physical reasons. But by filling many non-flying officer positions with experienced fighter pilots, we were able to achieve a ratio of two 'old-timers' 'for each new pilot.

As the newer replacement F-86s began to arrive, all of their pilots seemed to know what was going on in spite of the 'SECRET' classification of the move. Among these First Lieutenant Ralph D. Hoot' Gibson, who begged to be included. After discussions between the 4th and 56th commanders, 'Hoot' was transferred to the 4th FlW in record time. He was to become history's third jet ace.

Amid the frantic preparations, and even before the fighters left, some officers, airmen, and equipment began to depart, leaving only those persons and equipment needed to launch the Sabres. Maintaining a proper balance of people and equipment was crucial for a successful move. As a tribute to our hard-working maintenance crews I noticed that they all carried their tool boxes as personal baggage, making sure their birds would be ready to go.

On 11 November, F-86s from the three bases began heading West. Everyone, it seems, selected Wright-Patterson AFB for the first refueling stop. At 1100 hours, I led the last flight of my squadron out of Dover and headed for Wright-Patterson. We made the departure deadline but another crisis loomed ahead. Although the official orders NOW show that we were to be in place at our POE by 18 November, we were told that all aircraft had to be at those destinations by 13 November - just two days away! Anyone not making that deadline would be left behind.

I suspected that this was just a threat designed to encourage early arrivals, which was later confirmed. On the plus side, we were told that if anything - ANYTHING - was needed enroute, we were to use the name assigned to our operation - "STRAWBOSS" - to receive the highest priority. This was to include exchanging a badly broken F-86 for a serviceable one if the best base had Sabres. The magic word was STRAWBOSS.

At Wright-Patterson, the transient ramp was in chaos. Practically the entire group had chosen that base for the first refueling. But no one had alerted the folks at Wright-Patterson! To make matters worse, 11 Novemher was Armistice Day (now called Veterans Day) and a weekend to boot. Refueling 70+ Sabres by the undermanned transient crew was proceeding at a snail's pace. As the 4th Group Commander, Lt. Col. J. C. Meyer, approached my airplane I could see that he was furious He said I should have taken my squadron somewhere else to relieve the congestion at Wright-Patterson. Rather than point out that his staff should have handled this bit of coordination, I simply apologized. But it was clear to me that the 336th wouldn't be able to depart this day for the next leg.

On top of the refueling problems, one of our airplanes required an engine change. With the help of a tramsient alert crewmember, 'Mo' Pitts, my squadron materiel officer, began looking for a suitable engine. In one of the hangars, they discovered a flight test F-86A opened up for an engine change - with the replacement engine on a stand. After determining that the engine would work in our airplane, Pitts invoked the 'Strawboss' priority, and the engine was installed in our Sabre overnight by the WrightPatterson crew.

Next morning, Sunday, 12 November, flights of 336th aircraft headed west once again, but this time to a variety of bases We didn't want a repeat of the WrightPatterson overload. My flight departed last, heading for Sheppard AFB, Wichita Falls, Texas. On arrival thee, we needed still another engine change. Sheppard was a major maintenance training base, and after sending the rest of the flight on to Albuquerque, I began negotiating with the base commander to get one of their J47s installed in our sick F-86. He allowed that it was Sunday, but they'd get right on it the next day or so. Knowing this would be a disastrous delay, I called the USAF Command Post and used the magic word - "STRAWBOSS". Within an hour a crew showed up to perform the engine change. Magic word, indeed!

Early the next morning, the re-engined Sabre was ready. I decided to act as chase while my pilot flew the test hop. Gaining altitude in a wide circle of the field, I moved in tight and checked the test aircraft for signs of leaks. Once we were satisfied that the airplane and engine were OK, I headed us for Albuquerque, filing a flight plan by radio. We were on our way again.

Arriving at Albuquerque, I could see that some 336th birds were still there, while a large group had already departed for the next leg - Nellis AFB, Nevada. After an uneventful refueling, I led the remaining aircraft to Nellis to join the rest of my squadron. We were expected at Nellis and enjoyed a problem free turnaround. On departure, when the entire squadron was airborne, we made a formation fly by to bid farewell to many of our old friends in the fighter commurity. The flight to McClellan was relatively short, so we remained at a fairly low altitude in a wide spread formation as we passed over my home town of Stockton, California.

We made it to McClellan by the deadline, and ground crews immediately went to work preparing our airplanes for loading onto the decks of four oil tankers for shipment to Japan. This consisted, in part, of rubbing down all exposed surfaces with a heavy oil which was intended to minimize salt water corrosion. The pilots were bussed to Fairfield-Suisun AFB (now Travis AFB) for overseas processing involving an untold number of innoculations.

Then it was on to Haneda Airport, Japan, via MATS, finally ending at Johnson AB, the rear echelon base of the 4th Fighter Wing in the Far East. Then, the bulk of the 336th began to reassemble, since most had been airlifted across the Pacific about the same time as the F-86 pilots.

On 5 December, the first six 336th Sabres arrived by tanker at Yokosuka, Japan. They were transferred to barges and eventually off loaded at Kisarazu AB across Tokyo Bay. At Kisarazu, a maintenance team from the Far East Air Material Command (FEAMCOM), along with 4th maintenance crews, prepared them for flight to Johnson AB. The oil coating applied at McClellan had provided little protection, and severe corrosion and damage had occured during the voyage. The maintenance crews at Kisarazu worked diligently to repair this damage. On 8 December the First aircraft was ferried to Johnson AB, to be followed by many others.

On 13 December, exactly one month after arriving at McClellan, the first flight of seven F-86s departed Johnson for the trip to K-14 (Kimpo) in Korea near Seoul. Led by Lt.Col. Meyer, the flight was delayed by weather at Itazuke AB, Japan, eventually arriving at K-14 on 15 December. Most ground crews and some of the pilots had gone to Kimpo ahead of the aircraft so the 4th Fighter Group was ready for combat!

(from the editor: OK, so we got

your attention by alleging that the 336th Sabres used 'tankers' to cross the

Pacific. We apologize for raising your blood pressure because everyone knows

that the F-86 could not be refueled inflight: - could it? Although Col. Hinten

was too modest to mention it, there is a fitting postcript to his story. On

17 Decernbex, Lt.Col. Bruce Hutton Kored the first F-86 victory over a MiG-15

in the Korean War.)

SAVING THE SABRE PILOTS

The Undertold Story of Rescues in Korea

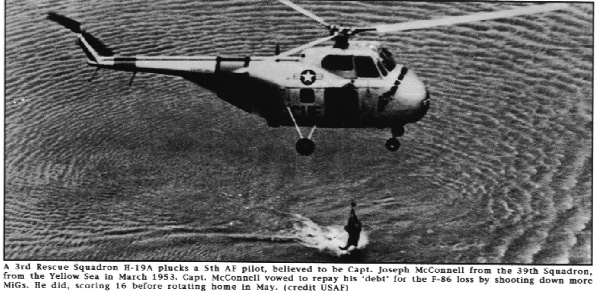

In looking back on almost ten years

of stories in Sabrejet Classics, one finds all-too-frequent mention of an

F-86 pilot heading out to sea, ejecting, and being picked up either by helicopter

or the SA-16 during the Korean War. Others couldn't make it back to home base,

but were rescued from deep in North Korea. Time and again, the rescue crews

did their job, flying into incredibly dangerous situations to save pilots

from an uncertain future in the hands of the enemy. In a sense, and using

present day vernacular, the rescue forces were a "force multiplier"

because the pilots they saved were returned to duty and flew many more combat

missions. Well known pilots such as Boots Blesse, Cliff Jolley, Joe McConnell

Lonnie Moore, Dee Harper, and many more were beneficiaries of the heroics

performed by the crews of SA-16s and helicopters of the 3rd Air Rescue Squadron/Group

and other helicopter equipped units.

Sabrejet Classics is happy to report that an authoritative and detailed account

of rescue operations in Korea is now available. Dr. Forrest L Marion, a former

USAF helicopter pilot, who is assigned both as a civilian historian and reservist

with the Air Force Historical Research Agency at Maxwell AFB, Alabama, has

written "Sabre Pilot Pickup: Unconventional Contributions to Air Superiority

in Korea." The article is carried in the Spring 2002 issue of Air Power

History, published by the Air Force Historical Foundation (AFHF). The Foundation

has an excellent web site at AF Historical Foundation , and copies of the

Spring 2002 issue of Air Power History can be ordered for $6.00 per copy (s&h;

included), by using their web site or contacting Col. Joseph A. Marston at

(301)7361959, or e-mail him at afhf@earthlink.net. Although space limitations

prevent us from printing Dr. Marion's article in its entirety, we are pleased

that the AFHF has granted us permission to reprint an excerpt from Dr. Marion's

work, and we have chosen his account of a rescue attempt, although unsuccessful,

which illustrates the bravery of the rescue aircrews and a particularly heroic

act by a Sabre pilot. Dr Marion writes:

But despite many successes, would-be rescuers also knew the pain of being

unable to retrieve downed fliers known to have been alive on the ground after

going down in enemy territory. On February 3, 1952, Lt. Charles R. Spath,

334th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron, was forced to abandon his jet over North

Korea. Later, a flight mate observed Lieutenant Spath on the ground. Using

his survival radio, the lieutenant reported that he was unable to walk due

to a broken leg. A friendly guerilla team located nearby, monitoring the same

radio frequency that Spath was using, decided to intervene. Four of the guerillas

reached Spath ahead of enemy soldiers also in the vicinity and moved him to

a secure location. Some time later, the guerilla team made contact with Fifth

Air Force intelligence personnel who began coordinating a rescue attempt.

Capt. Gail W. Poulton, an H-19 pilot in the 3rd Air Rescue Squadron, was offered

the mission, which would be particularly hazardous due to the high elevation

of the area. After several weeks of meticulous planning, the mission was a

"go". Because of certain pieces of information that had been coming

from Spath and the guerillas that somehow didn't seem to fit, Poulton was

concerned that the rescue attempt might already have been compromised. Unfortunately,

his hunch was correct. Approaching the intended pickup area, Poulton contacted

Spath by radio and asked him how many people were at the landing site with

him. Spath replied, "I don't know." Suspicious. Poulton said, "We

are here to pick you up, if everything down there is OK. You are giving me

uncooperative and unclear answers.... I have leveled off and we'll abort this

rescue attempt if you don't answer my questions fully ... in the next 15 seconds."-

Spath responded quietly, "You can chalk me off for saying this, but get

the of hell out of here, its a trap." Tragically, Spath died in captivity

some weeks later.

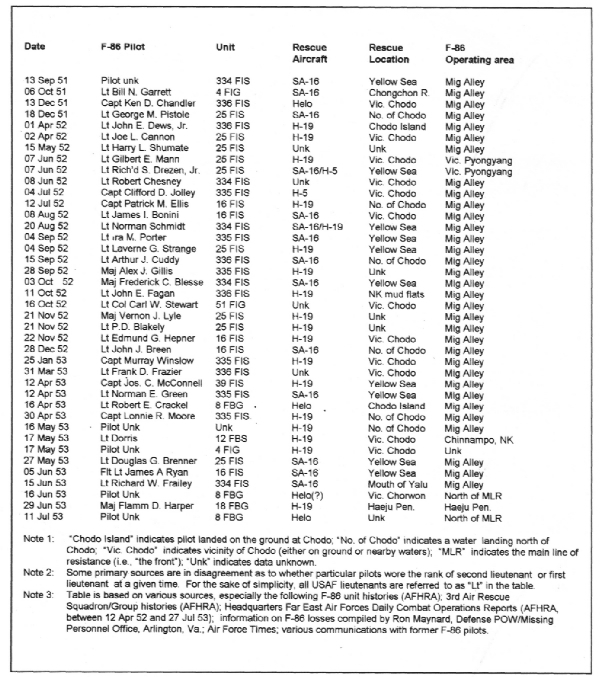

On a happier note, Dr. Marion has

included the above chart, which lists each rescued Sabre pilot and a few details

about the circumstances of his pickup.

Sabrejet Classics is indebted to the Air Force Historical Foundation for

allowing us to reprint a portion of their "Sabre Pilot Pickup" story.

We alsow ish to thank Dr. Forrest L. Marion for his excellent work.

SOS - KOREA

Sabre Pilots and Korean

Orphans

By Larry Davis

with help from

Joe Clark & Floyd Montgomery

When the average person hears the

words "Korea" and "fighter pilot" together, they naturally

think about swirling dogfights in the cold blue skies over MiG Alley. But

not every day was a good flying day. And fighter pilots didn't think and breathe

fighting the MiGs 24 hours a day, 7 days a week What did they think about?

Several pilots took it upon themselves to be humanitarians during a time of

war. What follows are two of many similar stories to come out of Korea.

When I began researching this story I knew of only one verified orphanage

story from the Korean War the well known story of Maj. Dean Hess and the orphanage

that he and his unit adopted during the early days of the war. I also had

a single photo of an unknown major with some Korean children near Suwon; and

unconfirmed reports of a pilot named Joe Clark who handled aid packages for

orphans in Korea. But I didn't know where or when. Now I know Capt. Joe Clark's

51st Wing story, and that of Lt. Floyd Montgomery and the men of the 58th

Wing at 0san.

Capt. Joe Clark arrived in Korea in November 1951, being assigned to the 16th Squadron at Suwon (K13). By tare January 1952 he had quite a few missions under his belt and was looking for more. During a lull in the air fighting, Capt Clark was listening to the Far East Radio Network and heard that his boss, Col. 'Gabby' Gabreski, had adopted an orphanage near Suwon in the name of his wing, the 51st Wing. It was the Yong Joo Jahae Orphanage located in a battle-damaged Budhist monastery on top of a mountain about 6 miles from Suwon.

A few days after the broadcast, Capt. Clark and another pilot visited this 'safe haven' with a jeep full of goodies candy, chewing gum, cookies, a case of oranges, some peanut butter, and bread. What Capt. Clark found changed his life considerably. Upon their arrival, the two pilots were met by Yoon Ho Soon, the orphanage Director, and Yun Han Kwan, his assistant - and about 340 Korean children. The children, obviously undernourished, looked at the two pilots with suspicion. They were standing outside the building in 34 ° weather without coats Many didn't even have shoes!

Soon the children saw that not only did the two Amertcan pilots mean them no harm, they bad food! They charged the two pilots and surrounded the jeep. Capt. Clark passed out verything they had brought with them within a scant few minutes. They were then shown through the rest of the 'orphanage'. The building had no heat, no furniture, not even beds. The 'medical room' was simply a room that isolated the sick children away from those that were well. They had no medical supplies. Warmth was provided by huddling together with the other children. The two pilots left Yong Joo Jahae later that afternoon, but not before promising that they would return with more help, much more help, and provisions and medical supplies.

Capt. Clark decided to enlist the aid of the people back home in the States. He sent a letter to Mrs. Lilian Finn, President of the Women's Club at Wright Patterscm AFB, where he had served prior to going to Korea. The letter was dated "Destitution, Korea, 27 January 1952". The letters were a simple appeal for help for these children. He sent similar letters to other Air Force wives clubs and VFW organizations. Sam Mrugal, Clark's old friend from Chicago, contacted the Chicago Junior Chamber of Commerce, and forwarded his letter to Austin Kiplinger of the Chicago Daily Neivs, who promptly read it on his nightly radio program.

The result was truly overwhelming. Within weeks, box after box started arriving at the Suwon Post Office, rapidly inundating the small staff and building. Capt Clark borrowed a deuce and half and made daily trips up Orphanage Hill to the old monastery. Mrs. Finn's group alone, sent over 150,000 clothing items and 24,000 lbs. of goods within the first couple of month. Capt Clark left Korea in October 1952. His efforts, as well as those of his squadron mates at Suwon, had made a big difference in the short lives of those Korean children.

Although the war in Korea 'stopped' on 27 July 1953, the plight of the Korean people did not ease for many years to come. And the men still serving in Korea. continued to attempt to make things a little brighter for all those who had been affected by the war. The men of the 58th Wing adopted the Sung Yok Orphanage located near Osan All (K-55).

Lt Floyd Montgomery, a pilot in the 310th Squadron at Osan, upon seeing the 96 children in the Sung Yook Orphanage, took it upon himself to try and provide some much needed clothing for the Korean kids that would be facing a very cold winter in just a few months. And we all know how cold those Korean winters could get.

Lt. Montgomery wrote to his mother, Mrs. Lillian DeMasters, a school teacher in Big Creek, California, and asking for help. The people of Big Creek, many of them school children themselves, responded with over 500 lbs. of clothing. The bundles were delivered to McClellan AFB within a couple of weeks, where a MATS transport was waiting to fly the badly needed winter clothing first to Tachikawa, and then on to Osan Lt. Montgomery loaded everything into a waiting truck and delivered the clothing to the orphans of Sung Yook.

The efforts of Capt Joe Clark and

Lt. Floyd Montgomery, and all the others that contributed their time and effort,

will be forever remembered by the children of Yong Joo Jahae and Sung Yook.

The F-86 Sabre Pilots Association salutes all those involved.

FLY FAST ... SIN BOLDLY

Flying, Spying & Surviving

By William P. Lear, Jr.

Addax Publishing Group

8643 Hauser Dr. suite 235

Lenexa, KS 66215

Bill Lear, Jr. is, of course, the

son of one of the most influential aviation figures in the 20th Century. He's

also a member of the Sabre Pilots Association. This is his autobiography,

and he's 'let it all hang out'. Much of his life can be described as 'truth

can be stranger than fiction', and just a few gems from his book will illustrate

this point.

Before he entered Air Force pilot training in October 1948, he'd already flown

a P-38 in two Bendix Trophy races. (Yes, you read that correctly!) There's

a story going around that Bill flew his own P-38 into Randolph Field to report

for duty'. The author denies this but describes his adventures as an ex-P38

pilot with over 1,000 hours flying time in a variety of aircraft as he submits

to instructional training from Air Force pilots.

Reviewer's note: Here, I must digress to report that at this point to Bill's book, I was prepared to "recuse" (popular legal term of this day) myself from doing the review as Mr. Lear names his instructors and flying mentors at Randolph, and wittingly or not, passes judgment on their instructional and human qualities. Since your reviewer had the same instructors in Class 50C a few months after Bill Lear, I suspected we might not agree on some points. Happily, I believe that we agree that these gentlemen represented the finest flight instructors of that or any time.

Although he was in (and out) of the Air Force most of his life, Bill Lear simply loved to fly. And fly he did an extraordinary mix of air machines. He never quite adjusted to the military life-style, but accepted its requirements (to a degree) in order to fly its great jet fighters. His entire life is a series of adventures too unbelievable for a Hollywood movie. And his autobiography reads like a who's-who of flying. You'll encounter famous persons, learn more than you want to know about Lear's personal life, marvel at his many, I mean MANY- near death experiences, and come away from his book feeling that you've met a very special man 'who did it his way'. Apologies to Frank Sinatra.

Highly recommended

review by Lon Walter