FIRST MAN,

LAST MAN

Fox Able 9

by Stewart S. Stabley

In January 1951, the 81st Fighter

Interceptor Wing was alerted for a 90 day TDY with the Third Air Division

in England. The deployment included the three combat-ready Squadrons of the

81st FlW - the 91sdt, 92d, and 93rd Squadrons, plus support organizations.

The original plan was for the wing to deploy from Larson AFB, WA, to England

in August 1951.

However, there would be a couple of changes before the actual deployment took

place. First, in July 1951, the movement was changed from TDY to PCS - Permanent

Change of Station. Second, the 93rd FIS would move to Kirtland AFB, NM, to

defend the Los Alamos Nuclear Laboratory. Their place in the deployment to

England would be taken by the 116th FIS, a Washington Air Guard squadron that

had been federalized in February. But first, the 116th had to convert from

F-51Ds to F-86As.

At 0450 hours, 13 August 1951, 25 F-86As from the newly transitioned 116th FIS, departed their home base, Geiger Field, WA. Col. Robert Garrigan, 81st Group Commander, led the formation, with Lt. Col. Frank Frost, the 116th Squadron Commander as second in command. The take-off was in two-ship elements, joining into flights of four for the first leg to Hill AFB, UT.

The weather was clear all the my, and the flights cruided cruised at 35,000' and .85 Mach. About 90 miles out from Hill, the Sabres began a throttle-back letdown. Col. Garrigan entered the pattern with about 257 gallons of fuel remaining after the one hour and forty minute flight from Geiger So far so good. Upon arrival, one pilot experienced hydraulic problems and his Sabre was towed off the runway. That aircraft remained at Hill and another was flown in from Larson to take its place.

At 0820, the remaining 23 Sabres departed Hill under CAVU weather conditions. One flight leader remained with the pilot whose Sabre was coming from Larson. One how and twenty minutes later, the 23 Sabres landed at Kirtland. At 1240 that Same day, they departed Kirtland for Tinker AFB, OK. The short (450 mile) hop to Tinker was made on top of a broken cloud deck in one how and twenty minutes.

The Sabres let down through a 5000'ceiling, which allowed everyone to log an instrument approach. The two pilots who had remained at Hill waiting for the replacement aircraft, rejoined the squadron at Tinker before the end of Happy Hour. The troops checked into on-base quarters, quaffed a few, had a good meal, and hit the rack. The first day of Fox Able 9 was history. At 0845 the next morning, the squadron, again at full strength, left Tinker for Wright-Patterson AFB, OH. Two hours later, despite a solid undercast all the way from Tinker, the squadron penetrated a 3000' ceiling and landed without incident. At 1300, the squadron was again airborne, minus one airplane that had a 'no-start'.

Next stop was to be Griffis AFB, NY. But within five minutes after take-off, two more J47s started acting up and both pilots returned to Patterson Field for repairs. One hour and forty-five minutes later, the remaining 22 Sabres began the let-down to Griffis. The weather had been heavy the entire flight, with clouds building to over 40,000'. The local conditions were deteriorating rapidly, and the last pilot touched down with a 500' ceiling and three miles visibility.

The 116th stayed at Griffis for an extra twenty-four hours because of weather along the leg to the next stop - Dow AFB, ME. But at 0820 on 16 Angust, the ceiling at Griffis lifted and the squadron was able to depart. At Dow, the ceiling had dropped to 900', but everyone was one the ground after one hour and fifteen minutes.

The weather looked good at around 1515, so the squadron left Dow and headed towards Goose Bay, Labrador. Weather was again a problem, with clouds up to 35,000'. But after passing the St. Lawrence River, the cloud deck went to scattered and landings were made at Goose Bay at 1650. Once again it was time for a little R&R.;

The "little extra R&R;" turned into six full days (and nights), as weather and communications problems at Goose Bay and Bluie West 1, Greenland, held up departure until 22 August. All the troops were plenty relaxed by that time. However, the delay allowed the Sabres that had remained at Wright Pat, to rejoin the squadron at Goose Bay.

Finally, at 1215 on 22 August, all 25 F-86As departed Goose Bay, on a course of 080º for Greenland. It was a nice sunny day, and the squadron made the flight to Bluie West 1 in an hour and thirty-six minutes. 'Duck Butt' #1 and #2 both came in loud and clear on the radio, as did the weather ship Yohe Baker. But the next leg on that same day would be somewhat different.

At 1810 (local time), the flights took off at five minute intervals, climbing on course for Keflavik, Iceland. Clouds built up to 38,000'. A three hour time zone change, which had not been anticipated, put everyone on night instruments for the last half of the flight. l/Lt. D.P. Sartz slid his F-86A in real tight on his leader, using only the wingtip and canopy lights as reference.

About 100 miles out, the squadron started its descent to Keflavik. After a 'tear-drop' letdown, they broke out at 600 feet in rain and darkness. The ceiling over Keflavik was down to 400'. But everyone made it after a flight of slightly over two hours. 1/Lt Kit Carson noted the local time - 2330 hours. He was thankful for the weather layover and some much-needed rest.

However, Col. Garrigan's sleep was interupted almost before it began. Slightly after 0100, a member of the airbase security guard awakened the somewhat fatigued colonel (and that's the worst kind!) informing him that a large group of communist agitators was at the main gate and were attempting to sabotage the F-86s. The security officer wanted Col. Garrigan to have his troops report to their aircraft and protect them.

Col. Garrigan, now completely lucid, politely informed the security officer, with an excellent choice of words, that base security was HIS job, and in no way was he going to disturb his nesting airmen. The following morning, the aircraft were under guard by Base Security and the incident passed.

Col. Garrigan, a nice enough fellow most of the time, seemed to have a penchant for finding trouble in Keflavik. While in a rest room at the airport, a German civilian waiting for a commercial flight, sneered at Garrigan, making some remark about the poor showing of the US Air Force during WW2. Garrigan grabbed the guy by his lapels, gave him a few shakes, and suggested that he (the German) let the past rest in peace. The German, wisely, left quietly.

On the 26th, the squadron departed Keflavik bound for Stornoway, Scotland. At least they started out that way. A total communications blackout forced a return to Keflavik. The next morning, all the 'Duck Butts' were in the air as the squadron again left Keflavik. The weather was clear and the squadron climbed to 35,000'. One hour and fifty minutes later, at 1025, the squadron touched down at Stornoway.

Remaining at Stornoway only long enough to refuel, the Sabres were airborne for the final leg of the Fox Able 9 journey. Next stop: Shepards Grove RAF Station, Suffolk, England. Two hours later, after a radio steer and a few flares from the Shepards Grove control tower (a WW2 technique), the 116th FIS located the base under an 8,000' ceiling. The time was 1520 hours, and Col. Garrigan had the distinction of being the FIRST F-86 Sabre pilot to land in England. There was no red carpet, only an RAF Vice Air Marshal and the 3rd Air Division Commander. The 116th had arrived at its new home.

The 91st and 92d Squadrons

On 11 September, 1951, Colonel Gladwyn Pinkston, 81st Wing Commander, led 50 F-86As from the 91st and 92d FIS out of Larson AFB, WA. They followed the same route as the 116th FIS had flown a month earlier. But the final destination was slightly different. Where the 116th had set up shop at Shepards Grove, the 91st was bound for RAF Bentwaters, while the 92d would join the 116th at Shepards Grove.

As it had been when the 116th had stopped there, a large group of communist agitators was waiting for the Sabres to land at Keflavik. However, Base Security was now well prepared and kept a good watch on the parked F-86s. However, security in town was not quite as tight.

There was only one gathering place in town, a night club of sorts. The free spending Americans seemed to be a constant source of irritation to the communists. Captain John Fink, a pilot in the 92d, was approached as he entered the club. He was confronted by a pink-faced, short, but stocky agitator, who walked up to the captain and said, "You US, me SU!" And then slapped Fink across the face.

In less than a second, the communist's comrades were picking him up off the floor with a bloody nose, and hurriedly escorted him out of the club. Captain John P. Fink was awarded the "Iceland Combat Medal", and was not allowed to buy a drink during the rest of the time that he was in Iceland.

On 2 October, "passing showers" stopped just long enough for Col. Garrigan to take the 91st Squadron to Stornoway, then on to Beirwaters. The 92d stopped at Stornoway, which resulted in more unexpected community relations with the locals.

The village leaders, upon learning that the Americans were going to stay until the weather cleared, re-scheduled their monthly Highland Fling for that night. All the village maidens, about fifty total, were bussed to the Community Hall. Transportation was also provided for the men of the 92d Squadron.

The Highland Fling lasted from 7 to 11 pm, with four bagpipers standing off to the side of the dance area, piping up a storm. The maidens danced like they never danced before. Between sets, they sat and waited for the handsome Americans to ask them to 'fling'. Most of our men were sporting brand new ankle-high, wool-lined boots which had been bought in the village that afternoon, much to the delight of the local merchants. The maidens put on a magnificent display of athletic skill, easily out-performing and out-lasting even the fittest of the Americans. 2d/Lt. Jim Adams was the last to go down.

The local males didn't dance - they drank! The few who were there, were huddled around a small wooden bar at the end of the hall, guzzling Scotch, and getting very drunk. About once every 30 minutes or so, they would become very boisterous and shout at each other, nose to nose. The bar tender would then close the bar, pick up all his bottles, and walk out through a doorway behind the bar. Fifteen minutes later he was back and all was calm - for another 30 minutes.

All the while, the bagpipes were screeching and the maidens and Americans danced wildly. The maidens said hardly a word. They just kept dancing and dancing and dancing. Finally about 2230, after a particularily raucous argument among the Scottish men, the bartender packed up his bottles and left. This time he didn't return. And promptly at 2300, all the maidens, as if on cue, lined up and marched out of the hall to the waiting buses. The Americans also returned, without delay, to their quarters. The next morning, 3 October, as anticipated, the weather at Stornoway was good enough for flying. Col. Pinkston flew into Stornoway to lead the 92d Squadron into Shepards; Grove. The British air bases had no published 'let-downs', and were difficult to identify, because all the old WW2 RAF bases looked very similar. Additionally, the ceiling was hanging at 800', with a 2 mile visibility. But Col. Pinkston got all the 92d pilots on the ground at the Grove following the two hour flight from Stornoway.

All except one - your author, I/Lt Stewart Stabley I had started out with the 91st Squadron, but was forced to join with the 92d at Keflavik when my engine wouldn't start for the leg to Stornoway. I made the penetration into Shepards Grove with the 92d, then took up a heading for Bentwaters at 500' to rejoin the 91st. A radio steer and a flare had me on the ground at Bentwaters in a scant few minutes. S/Sgt V.D. Gunder, crew chief on my P-86 (#48-300) gave me a big grin and a hand shake as the turbine was winding down. He informed me that I had the distinction of being the LAST Sabre pilot of Fox Able 9 to land.

I immediately thought of my wife,

Nancy, who was about to give birth to our second child. That evening, I sent

her the following telegram: "WUA 10417 PD INTL FR=CD WOODBRIDGE VIA RCAOCF

3 1951 1850 = MRS STEWART STABLEY JUNIOR = 66 EAST HIGH ST RED LION (PENN)

= ARRIVED TODAY STOP CABLE ME ON B DAY STOP MY LOVE = STEW". Our daughter

Sue Ann was born ten days later on the 13th of October 1951. FOX ABLE 9 had

been a complete success and the first US Air Force F-86 wing was in place

defending Europe against the vaunted Soviet MiGs.

FLYING WITH THE ROYAL DANISH AIR FORCE

by Ralph D. Waddell, Jr.

In the Spring of 1958, the US Air

Force transferred thirty-eight F-86D-35s to the Royal Danish Air Force. The

aftcraft had undergone total rehab and were delivered as zero time' airframe

and engine. They had been 'cocooned' in a rubberlike sheeting and were transported

to Denmark aboard a US Navy aircraft carrier. There, they were towed from

the dock in Aalborg, Denmark, to the Royal Danish Air Base north of the port

city.

Five pilots and fourteen maintenance men were sent TDY from the 86th Fighter

Interceptor Wing in Germany, to assist in the delivery of the aircraft and

in the training and checkout of the pilots and ground crews of two Danish

fighter squadrons - the 726th and 727th Eskadrilles. Prior to the conversion,

the 726th had been flying the Gloster Meteor NF-11 all-weather intercep and

the 727th was flying Republic F-84E Thunderjets.

I was one of the five pilots sent to the Danish base. I was with the 496th FIS at Hahn AB, Gemany. The others were Glen Noyes and Jerry Lawhorn from the 526th FIS at Ramstem, and Russ Grant and another pilot from the 525th FIS at Bitburg. The unidentified pilot returned to Germany shortly after we arrived in Denmark. He was involved in the 525th FIS conversion to the Convair F102A, that had just started. Glen Noyes was the Commander of our little detachment. The maintenance men all came from 86th FAV resources. They were joined by a small group of aircraft, engine, and electronic techni representatives from the various companies that built the F-86D.

The first order of business was getting the 'cocooned' aircraft flying, and start training the ground crews. Flight crew training began as soon as the flight simulator was available. As the aircraft were made ready, they were test flown by our pilots, then turned over to the ROAF crews. We then started the Danish pilot checkouts. The transition was mostly uneventful. The 726th Squadban Commander was the first pilot to checkout in the F-86D. I flew chase on his first flight and it went very well. The new pilots were all very anxious to get their 'Mach Buster' pin. On an early checkout mission, we chased them through the Mach, and the North American Tech Rep met them on the ramp to award them their pins.

In early Fall, Glen and Russ returned to their squadrons in Germany. I took over the detachment. Jerry and I stayed until the end of December. By this time we had two RDAF pilots who had just completed transition at Perrin AFB, Texas. They were immediately incorporated into the training cadre. We continued to fly maintenance test flights and transition chase flights. By December, we were ready to turn over all flight training operations to the two Danish fighter squadrons, and Jerry and I returned to Germany in late December 1958.

Due in very large part to the early efforts by the 86th Wing, and Glen Noyes' planning preparation for the transisition, the conversion program went very smoothly. We had very few aircraft incidents. However, in the late Fall, we did lose an aircraft. As many of you may remember, the canopy latching handle on the -35 model, was on the floor. A student pilot, with an RDAF pilot flying chase, was maneuvering when his flight suit became 'involved' with the latching handle. The canopy suddenly left the aircraft - and the student decided to follow the canopy!

In subsequent years, the Danish Air Force received additional F-86D aircraft from the US. They also modified their 'Dogs' in various ways, including installation of the Martin-Baker ejector seat, and the inclusion of AIM-9 Sidewinder launch equipment.

I could not have asked for, or

received a better assignment than the six months of temporary duty in Denmark.

The work was great. And the Danish people, both military and civilian, were

a delight to be around and work with. I haven't been back to Denmark since

then, but I sure look forward to a return trip someday.

YUMA JUDGE

by Bill Shields

Don Jabusch, wrote "Sabre

D Tales" in the Fall 1999 issue of Sabrejet Classics, doesn't know how

lucky he was not to have me as a chase judge in the 1955 rocketry exercises.

A bunch of from all over Air Defense Command, were sent to Yuma for this duty.

This was a real vacation from the Pittsburg weather. (I was with the 71st

FIS at Pittsburg Airport.) Plus, it was a lot of fun.

A typical mission consisted of fifteen minutes of chase judging, and about

forty-five minutes of buzzing and acrobatics. The chase aircraft were nothing

to brag about, being ancient Dash-1 D models, with the radar replaced by lead

weight to maintain the CG. But flying any type of jet aircraft sure beats

anything happening on the ground. Why was Jabusch lucky? Because he wasn't

flying one late morning mission that I was chasing. The weather was good,

with a few cumulous clouds beginning to build up on the edge of the range.

I could see the B-29 target tow ship, chugging along out there about thirty

miles or so. The F-94 (that I was chasing) had good radar contact, and all

was going well. That is, until I saw that the clouds were starting to build

up to our level.

"Well", I'm saying to myself, "This is a good run. And that cloud probably isn't going to get in our way. And this is an all-weather Air Force. Those guys shouldn't be bothered by a little cloud. Besides, there are two of them, and they're under the hood and probably will never see it"

Murphy's Law didn't fail me. At about forty seconds out, it was very clear that we were going to be very close to that cloud. Still, my impeccible logic about 'the all-weather Air Force', and being 'under the hood', and so forth, held. We pressed on. At about twenty five seconds to go, it became even more clear that we were headed for some type of cloud encounter. I couldn't afford to lose sight of the tow ship, so I popped up about a hundred feet or so. The F-94, shall we say, 'brushed through" the plume on top of what I now knew was a thunderstorm. And they got a real good 'bump!'

I claim that it was all perfectly safe. I never really lost sight of either the Starfire or the B-29. In another second I was right back on the F-94s wing. However, the F-94 crew thought otherwise. Their reaction was first evident when the edge of the rear hood raised up a couple of inches, and two beady little eyeballs peered out at, first me, then the cloud. The rest of the event is a bit hazy. But if memory serves me correct, I cleared them to fire. They did - and they missed.

It turned out that I had not drawn just my old F-94 crew, but no less than a group commander - Colonel Ben king. This absolutely, positively guaranteed that the matter would be brought to the attention of my TDY Boss, none other than the well-known Major James Jabara. It was!

Colonel King demanded a repeat mission, plus a full explanation of the circumstances. I will omit the sordid details, other than to say that I found Jabara to be a reasonable man, who did not fire me on the spot and send me back to Pittsburg. But we did agree that, in the future, it would probably not be a good idea to get so close to a cloud.

So Don Jabusch lacked out by being

elsewhere on that day. Colonel Ben King did not. I hope he is not a member

of our Association (he isn't) so that I won't have to "explain myself

all over again.

INTERCEPTOR WEAPONS SCHOOL

by Sabrejet Classics Staff

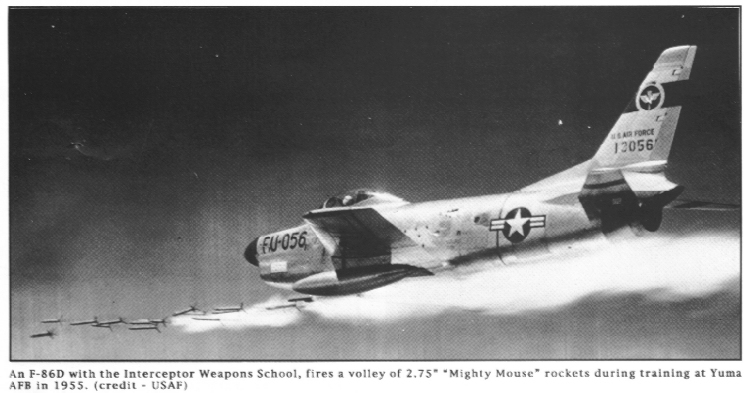

A photo appearing in Sabrejet Classics,

Fall 1999, showing an F-86D of an unknown unit at Tyndall AFB solicited several

responses from the membership. The question "Who were they?" was

answered with the identification of the airplane as one from the Interceptor

Weapons School from Tyndall AFB, Florida, officially known as the 3628th Combat

Crew Training Squadron. Several members filled in some of the unanswered questions

about the Interceptor Weapons School. Thanks to members Bill Creech, Paul

Jones, and Erwin Wallaker for their contributions. The following is based

on information received.

The Interceptor Weapons School (IWS) was established at Tyndall AFE, Florida

on I February 1954 with Major John Nelson as Commander. Initially it was called

the Interceptor Weapons Instructor School. Schools for all three major types

of interceptor were established at Tyndall at the time - the North American

F-86D, Northrop F-89 Scorpion, and Lockheed F-94 Starfire. During the first

year of operation, the F-89 and F-94 schools were transferred to Moody AFB,

Georgia. The F86D school opened on I July 1954.

It wasn't until 31 December 1955 that the IWIS was renamed as simply the Interceptor Weapons School or IWS. Both the IWIS and the IWS were under the control of the 3628th Combat Crew Training Squadron, 3625th Combat Crew Training Wing (Interceptor). On 1 July 1957, Tyndall AFB was transferred to Air Defense Command the IWS came under the control of 73rd Air Division (Weapons), 4756th Air Defense Wing.

For the next six months, the aircraft and crew training was conducted by the 4757th Air Defense Squadron (Interceptor Weapons School), which was redesignated the 4757th PAIS on 1 November 1957, then renamed the 4757Lh TWS on 15 December 1957. Ala, the IWS replaced the F-86Ds with Convair F-102As on 30 December 1957.

The mission of the IWS was "To train flight command/ instructor pilot quality students to be able to teach and demonstrate any all-weather tactic that the aircraft was capable of performing." The IWS was in operation during the entire life of the air defense mission as qualified by Air Defense Command and later Aerospace Defense Command. When ADC was incorporated into TAC on 15 October 1983, the IWS was shut down.

With the mission of the IWS clearly stated, the instructors and students developed various tactics that could be flown against any 'bad guys' that might attempt to penetrate the air defenses of the United States. Each unit sent a pilot and Ground Control Intercept Controller to the IWS at Tyndall, where they were trained in the latest interceptor tactics, before returning to their units to pass on the information they had learned at Tyndall. The instructors at the IWS considered themselves to be the 'elite' of the all-weather interceptor business, as they were always ready to try something new and different. The instructors developed tactics to counter the electronic counter-measures anticipated by the Soviet bomber forces, perfected night firing on multiple target situations, and regularly flew (illegally) in weather with out an available alternate whenever their area of operations was socked in. The IWS instructors literally pushed the envelope Of all-weather tactics to the limit (and beyond) of safety.

The IWS had students flying both daylight and night intercepts, with a live-fire exercise at the end of each session. The night intercepts were especially interestIng as the target was usually at about 1500 feet over the Gulf Of Mexico. The F-86D pilot would come in at about 500 feet to plot the intencept. This was often necessary because Of the failure of the Hughes E-4 Fire Control System, which had a tendency to 'break lock' at just the wrong time,

As interceptor aircraft progressed

from the F-86D era to the Century series of double-sonic interceptors like

the McDonnell F-101B Voodoo, the Convair F-102A and F-106A delta-wing interceptors,

and the Lockheed F104A Starfighter, the IWS instructors developed and refined

the tactics for each new type of aircraft. This was true up through the use

of the F-4 Phantom and the F-15 Eagle.

THREE SABRES DOWN!

The Worst Sabre Accident?

By Lon Walter

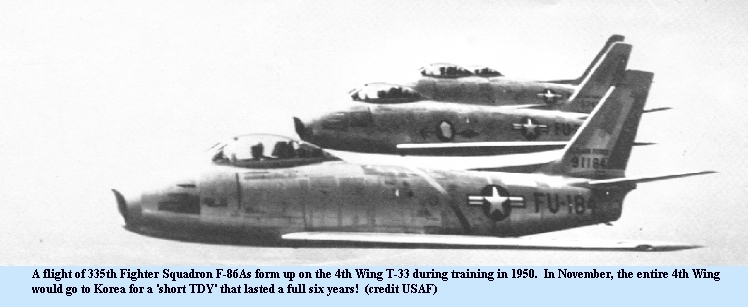

The 4 1/2 months between the start of the Korean War, on 25 June

1950, and the deployment the 4th Fighter Intercepter Wing to Korea were remarkable

in several ways. When the war started the wing was based at Langley AFB, VA.

Almost immediately in response to a perceived threat to the nations capitol,

its three Fighter squadrons deployed - the 334th to New Castle County Airport,

DE; the 336th to Dover AFB, DE; and the 334th to Andrews AFB, MD; near Washington,

DC. At these locations each squadron maintained an air defense alert posture

aid scrambled fully armed F-86A to investigate unidentified aircraft approaching

the east coast of the, US. Normal training although secondary to the air defense

mission, Continued. This training concentrated mainly on qualifying an influx

of newly graduated pilots on the Sabreo and making them combat ready. All

of this ended on 11 Novembier 1950, when the entire wing began a deployment

to the Far East This story describes the most dramatic event of the June-November

period.

For the 335th Fighter Interceptor Squadron, the morning of 18 October 1950

began as most others in the preceding three months. The two F-86A-5 Sabres

on 5 minute alert were positioned near the end of the main runway at Andrews,

while pilots and ground crew waited in a nearby shelter for scramble orders

from the air defense control center. Two other Sabres were on an extended

cross-country training flight to the west coast. The local flying program

was filled with such missions as two ship instrument training, formation flying

practice, simulated gunnery training using cameras, and round-robin cross

country flights. The pilots of the 335th ranged from experienced combat veterans

of World War II, to the newest graduates of the Air Force flying training

program.

The flight scheduling board showed one of the earliest flights was to be led

by Ist Lt. Joseph W. Russell, a recent arrival, but a relatively experienced

F-86 pilot. He had been away from the squadron on temporary duty since before

the move from Langley. His wingmen were 2nd Lts. Luther C. "Bloop"

Barcus, and Cornelius P. "CP" Mills. They were scheduled to fly

F-86As nos. 48-248, 48-266, and 48-268. Both Barcus and Mills were brand new

pilots with no more than 40-50 hours each (all in the F-86) since graduation

from flying school. The mission was formation training and camera gunnery,

meaning that either the flight members would engage in simulated combat maneuvers,

or would take turns making 'pursuit curve' camera-gunnery passes on each other.

It was a typical Fall day in the area around Washington, with patchy ground fog and haze, and a thin layer of clouds above, giving way to blue skies at about 10,000 feet altitude.

As the flight climbed out form Andrews, 'CP' Mills might have glanced over towards the nearby Virginia landscape. A 1949 graduate of Virginia Polytechnic Institute (now Virginia Tech), he had been born and raised in nearby Northern Virginia, and his parents still resided there. Most training flights lasted about 80 minutes, and the three Sabres climbed in a "V" formation to the training area over Chesapeake Bay. There they accomplished their assigned mission, then rejoined for the return to Andrews.

According to Barcus, the three aircraft were letting down over the Potomac River (they were actually about 8 miles south of Quantico) for a landing at Andrews, when they ran into a haze layer at about 1,000 feet. As they continued their letdown, Barcus was concentrating on flying a tight formation when he saw two 'explosions' where the other two Sabres had been. Simultaneously, he was stunned by what felt like his F-86 had hit a brick wall. (p) When he regained his senses, his Sabre was alone in the sky, and was severely damaged and barely flying. Barcus, still somewhat woozy, realized he needed to find Andrews quickly and get his damaged airplane on the ground. He radioed Andrews that he thought his two companions had crashed. He was unable to get the radio compass (the only radio navigational aid installed on the F-86A) to work, and his gyro compass was acting strangely. He flew in a direction he thought would take him to Andrews, but he was actually flying away from the base. When he ran out of fuel, he found a farmers field near Aden, VA, about 30 miles southwest of Washington, and landed wheels-up. The aircraft was reduced to rubble, but miraculously, Lt. Barris was found staggering around by two farmers. He had suffered a broken leg and multiple cuts, and was taken to the hospital at nearby Quarnico Marine Base. He recovered, but never rejoined the squadron.

Although no one can ever be certain about what caused the loss of the three aircraft, several theories can be postulated:

With the aircraft in a tight "V" formation (it is also conceivable, but less likely, that they were in echelon formation) the wingmen, both fairly inexperienced, would have been concentrating on the leaders airplane - and probably were not monitoring their own flight instruments. The leader, himself with little recent F-86 time, let down into the haze expecting to catch sight of the ground at any moment. Undoubtably, the flight was in a turn, with Barcers' aircraft on the high side. The turn would have had to be shallow, and the rate of descent quite low, as Joe Russell searched for the ground. The two 'explosions' witnessed by Barcus, were Russell and Mills hitting the Potomac River. Barcus' own aircraft 'ricocheted' off the water and was thrown back into the air.

Another theory is that the the flight leader misread his altimeter by 10,000 feet. The analog altimeter installed in the F-86A, could be misinterpreted by an inattentive or inexperienced pilot. Although it was common at night or in severe weather, several accidents (not all of which were in F-86s) in those days, were attributed to a pilot letting down through what he thought was 10,000 feet, but was in fact, 0 altitude! One aspect of this theory which lessens its credibility in this case, is that if the flight leader thought he was letting down through 10,000 feet, his rate of descent would have been so great that Barcus aircraft would almost certainly been destroyed by the impact with the water. It was a tragic day for the 335th, which was described by the Washington Post in its report of the accident, as a 'crack outfit'. The remains of Russell and Mills were recovered from the Potomac, and members of the squadron consoled the Mills family in nearby Virginia. We know of no other single accident that involved the loss of 3 or more F 86 aircraft.

The author would like to thank

Larry Davis, Dick Merian, and John Henderson, who provided details essential

to the telling of this story.

TAIL ZAP

THE RCAF VISIT

TO THE 496TH FIS

AT HAHN

by Ralph Waddell

During the late 1950s, the 496th

Fighter Interceptor Squadron, stationed at Hahn All, Germany, established

an on-going association with the RCAF fighter squadron at Marville, France.

RCAF No. 439 Squadron was flying the Canadair Sabre Mark 6. On many occasions

while on local missions, we would find ourselves confronted by several Mark

6's and friendly air combat maneuvering training would ensue, i.e. 'Rat Race'!

A very friendly rivalry was established between the 496th pilots in their

D model Sabres, and the RCAF Mark 6 pilots.

We also scheduled social visits to their base, and they would visit us at

Hahn. I remember one of their visits to Hahn very well. It was in the spring

of 1958. The Canadians flew an afternoon training mission and recovered at

Hahn. Our maintenance crews took care of their aircraft, while the pilots

gathered at the Officers Club with us. It was a night of good fellowship,

a good dinner, and some social drinking. All in all, a grand evening. It culminated

with a parade through the Hahn housing area at about 4 in the morning - led

by a Canadian pilot playing a very LOUD bagpipe. We heard about this from

base personnel numerous times during the next several weeks.

In the meantime, our maintenance and alert crews had been busy on the flightline. The tail flash on the Mark Es was a large Sabre-Tooth Tiger on the camoflaged aircraft. The tail flash on our 496th F-86Ds was black and golden yellow emanating from the apex of the rudder. But during the night, while both the Canadian and 496th pilots were enjoying themselves at the O-Club, all the RCAF aircraft were repainted with the 496th tail flash colors.

Imagine the surprise of the Canadians when they came to the flight line the next morning to head back to Marville. Later, I was told the hardest part was convincing the Marville tower operators to let them land once they got home! Of course, we subsequently visited Marville to reciprocate the visit of the Candian pilots. Knowing they would retaliate, and not being stupid, we flew down in our C-47, leaving our aircraft at home. All except for the T-33 flown down by our Operations Officer. The next morning, we awoke to find the T-Bird painted a glorious red, with a large Sabre-Toothed Tiger flowing all the way down the side of the aircraft. It was truly a thing of beauty.

They bad gotten us back in a big

way. However, them was one difference. When we painted the tail flash on the

Mark 6s, we had used water paint so it could be removed without too much trouble.

But our T-Bird was painted with enamel, and it took a lot longer to remove

it.