PURSUING A SABRE,

BUT DOGGED BY A BOXCAR!

by Gerry Martas

With barely 30 hours of Sabre time, I did not expect to ever have anything to say in Sabrejet Classics. The article, "One Short Tour" in the Spring 1998 issue, however, provided an opening to add to Kingsley Purton's recollections.

That Summer I was a new member of the 93rd PBS, 439th FBW, at Selfridge AFB, Michigan. The 439th FBW was brought to active duty training, 3-17 August 1957, by AF Reserve Order #140, dated 28 June 1957. Squadron personnel traveled to and from the F-8611 training site in Memphis, Tennessee, on chartered four-engine airliners. For someone just recently off of active duty, this created the impression that the Reserves really operated First Class.

During that initial tour of AF Reserve duty, I eagerly looked forward to a checkout in the F-86 later that summer. First, along with one other lieutenant, I would have to complete the jet refresher syllabus in the T-33 Shooting Star. Our jet time consisted only of the eighty training hours flown at UPT, and I'd been flying C-119 Flying Boxcars on active duty.

The first week went exceptionally well, with plenty of flying. Then, unexpectantly and suddenly, the Secretary of Defense, took $5 billion away from the Air Force budget (about $45 billion in todays dollars!). For nearly a week, almost the entire Air Force ceased flying until the impact of this unprecedented action could be translated into 'flying hours remaining'.

A corollary ramification was the quick transfer of all fighter aircraft out of the Air Force Reserve and into the Air National Guard. Henceforth, the AF Reserve was to be relagated to flying transports!

By Christmas 1957, with C-119 'Flying Boxcar' transition well under way at Selfridge, several lieutenants and a few captains managed to transfer to Air Guard fighter units. For me, it was across the state line to Toledo, Ohio, where the 112th FIS was to re-equip with Republic F84F Thunderstreaks. (The freedom and ability of Reserve pilots to 'shop around' for fighter slots, and to choose civilian jobs to enable them to fill those slots, or resign, may surprise our active-duty-only counterparts.)

Three years elapsed before another opportunity arose for me to check out in the F-86 Sabre. In the Spring of 1960, after qualifying to fill a vacancy in the 137th TFS, New York Air National Guard (who were equipped with F-86Hs), I accepted civilian employment in New York. My goal to fly the Sabre was finally achieved. But my elation was brief. In January 1961, 1 received orders to go a Century Series airplane. The 137th was one of the first and few Air Guard squadrons ordered to convert to - TRANSPORTS! And incredulously, it was again to the C-119! It seemed like that machine, which I had flown on active duty, was persevering to do to me what its US Marine designation (R4Q2) sounded like.

I parted from the Air National

Guard until I was able to obtain another fighter slot some months later.

B-29 ESCORT IN KOREA

1 Lt Robert Makinney,

334th Fighter Interceptor Squadron

8 July 1951, Suwon, AB

The afternoon mission on 8 July was a bomber escort mission for B-29 Superforts attacking the Pyongyang area. This would be my fifth mission of the war, although I hadn't seen any Migs so far. We left K-13 to the south, in elements of two, joining up in squadron formation as we made a 180 turn, passed to the east of Suwon and started north in a 16 ship formation.

I was assigned as wingman to Col. Frands Gabreski, the famous World War Two ace, who had recently been assigned as Deputy Group CO of the 4th. He would lead this mission, and his call sign was Dignity Mike, or Dig Mike for short. Naturally, mine was Dig Mike 2.

We climbed out on a northwesterly heading, crossed the Haeju Peninsula, and leveled off at 25,000 feet. We rendezvoused with the B-29s as they crossed just north of Chinampo, near the mouth of the Taedong River. We crossed over the B-29 formation and immediately set up a race track pattern to the north of the B-29 flight path. Approaching the target, the radio chatter intensified, and we began to see puffs of dirty black smoke -flak - both above and below the B-29 line of flight.

The bomber commander - call sign Jakeman - announced - "Dignity, this is Jakeman. We are at 'Windy', which was a point in the sky five minutes from 'bombs away. This was also an advisory call to the flights of F-51 Mustangs that were attacking the flak batteries positioned near the target. When Jakeman called 'Windy', the Mustangs started to head out. As soon as the B-29s had crossed the target and released their bombs, we made a turn to the south. Filter Lead, the F-51 flak suppression flight, suddenly called - "Dignity, this if Filter Lead. We have bandits in the area!" We continued our escort pattern until the B-29s were well out of the target area. Gabreski called the bomber formation - "Jakeman, this is Dig Mike Lead, we have you clear of the area. We'd like to break off and go help Filter."

Jakeman replied - "Roger, and thanks!" Gabby made a hard turn back toward Pyongyang, and called the rest of us - "Dig Mike, drop tanks, and let's go to 100%" With the increase in power and having lost the drag of our drop tanks, we started to accelerate immediately, and initiated a climb to altitude. Within a few minutes, we were nearing Pyongyang from the southeast at about .92 Mach, and going through 30,000.

Without warning, Gabby dropped his nose and brought his power back to idle. It was obvious that he'd had a problem or had seen something. It was the latter, and I still hadn't seen a thing. We were now in a shallow dive, and had actelerated to about the F-86s max speed, descending through 20,000 feet. Gabby started firing at something, something that was at an excessive range. I could see the smoke around his gun ports., blowing back across his fuselage. But I still couldn't who he was shooting at.

I slid in closer to Gabby's tail as he fired a second burst, about 50-60 feet below and behind him. There it was, a MiG. I could see Gabby's tracers light up the MiG all along the trailing edge of his right wing. The MiG pulled up sharply, and Gabby followed, firing again, and agin scorng more hits on the MiG fuselage. At this point, with his greater airspeed because of the dive, Gabby overshot the MiG, sliding past him.

I maneuvered my Sabre into a position where the Mig was in my gun sight. I was sorely tempted to fire, but instinctively thought that it was Gabby's kill, not mine. More importantly, I was a wingman. My leader was ahead of me and needed me to keep him clear. Without another thought, I added power, slid past the MiG and rejoined Gabby, whom I still had in sight in my peripheral vision.

As I flew past the MiG, he had rolled inverted, starting an almost vertical dive. I was sure he had lost his engine and would ultimately crash. With that I rejoined with Gabby, who was in a right turn looking for other bandits. I had just regained my position on Gabby's wing, when he again dove for the deck. This time though, the descent was much more gradual. As we leveled off at about 6,000 feet, he opened fire at a MiG at a range of about 1500 feet.

I watched as numerous pieces of the MiG's tail started to come off as Gabby's rounds found their mark. The MiG took no evasive action, continued a slight descending path, crossed the Taedong River, and crashed into a hill on the south bank. At this point, we were both at a very low altitude, both at Bingo fuel, and the radio chatter had subsided to the point that it was obvious the Migs had left, and we started for home.

As we climbed back to altitude

enroute back to Suwon, I asked Gabby - "Was that two?" He replied

- "Negative." And said nothing further all the way back. At the

debriefing, he explained that he had attacked a single MiG, which dove for

the deck and leveled off, probably hoping to escape another beating like the

one he had just sustained. But Gabby saw him again. It's highly unlikely that

he'd have been able to make the 100 mile flight back to Antung anyway. Gabby

got the kill and I was a good wingman, which is what they were paying me for

at the time.

THE FRENCH AIR FORCE & THE F-86K

by Jean-Marie Dieudonne

The F-86K was an all-weather interceptor

developed by North American for use by NATO air forces in Europe. Based on

the F-86D-40 airframe, the F-86K did not have the highly complex Hughes E-4

Fire Control System, although it did use the same radar. Air Force felt the

E-4 FCS was far too complex and classified for use by NATO. Therefore, North

American developed the MG-4 Fire Control System, a much simpler unit to maintain,

that used the readily available, easily maintained, and highly accurate, type

A-4 lead computing gunsight.

In addition, the F-86K would not be armed with air-to-air rockets as on the

F-86D, instead having four M24A-1 20mm cannons, with a cyclic rate of 700-800

rounds/ minute. There were no provisions for carriage of any type of underwing

ordnance. However, beginning in 1959, many F-86Ds and Ks in service with non-U.S

air forces, were modified to fire the GAR-8 (AIM-9) Sidewinder heat-seeking

air-to-air missile.

The first of 120 production F-86Ks built by North American Aviation, was delivered to the U.S. Air Force in May 1955. The majority of the North American production run was delivered to Norway and The Netherlands Air Forces. But the main production would be provided by Fiat of Italy. Fiat built a total of 221 F86Ks, plus taking taking delivery of the two initial protype F-86Ks, for a total of 223 aircraft. The Italian Air Force received 65 Fiat-built F-86Ks; France took delivery of 60 of the Turin-built Ks; and West Germany received 88.

It is the 60 F-86Ks that were delivered to France in 1957 that Sabre Pilot Jean-Marie Dieudonne was very familiar with. "I graduated in U.S. Air Force Pilot Class 53G, flying the T-6 Texan at Kinston, North Carolina, then the T-28 Trojan and T-33 Shooting Star at Bryan AFB, Texas, had gunnery training in the T-33 at Del Rio, Texas, then to Luke AFB, Arizona to fly the F-84E Thunderjet."

"The Armee de l'Aire (French Air Force) received 60 F-86K Sabres that were split into two squadrons - Escadre de Chasse 1/13 "Artois", and 2/13 "Alpes". We were the only squadron in the Armie de l'Aire classified as "Tout Temps", or all-weather fighter. The first squadron, EC 1/13, was created in 1956 at Lahr AB in West Germany. We had twelve pilots that initially were sent for an advanced instrument flying course since we were all coming from day fighter squadrons."

"Our first commander was Colonel Risso, a survivor and great fighter pilot from the French squadron that had operated in Russia during World War 2, known as the Normandie-Niemen Squadron. In late 1956, EC 1/13 began receiving the first of 8 brand new Lockheed T33 Shooting Star jet trainers, along with the F-86K simulator. The U.S. Air Force supplied two instructor pilots, Captains Linn and Evans, and we were under the overall command of Major Hill. By that time we started to gain more pilots, and we were charged with making them more profident in instrument flying using the T-33s and the F-86K simulator."

"About the same time as the simulator program began to end, the first of our brand new Fiat-built F-86Ks began to arrive at Lahr AB. This is where the exciting part began - flying that marvelous aircraft. I made my first flight in the F-86K on 11 February 1957.

"It was about that time that we moved from Lahr AB, West Germany, to the eastern part of France and a new airbase - Colmar Myenheim. Here we received the rest of the 60 F-86Ks and we split into the two operational squadrons, EC 1/13 and 2/13."

"Most of our training missions in the F-86K at this time were aircraft identification in both daylight and night-time conditions, and in all types of weather. Often, we would take off from Colmar, make a training intercept, then land at either a U.S. Air Force or RCAF base in West Germany, where we would refuel, then take off for another intercept before heading for home at Colmar."

"Once we became fully combat operational, we would sit alert at one end of the runway at Colmar. The alert pilots lived in tents both during summer and winter. (We had some USAF F-86D pilots visit us, standing alert beside our F-86Ks and living with us in tents during the winter. We didn't see them again so we knew it was very uncomfortable.)"

"I recall that we scrambled several times on one Czechoslovakian IL-18 airliner that was flying from Paris back towards the east. The guy would never follow the flight plan, and we suspected he was taking infrared photos of restricted areas. But he knew where he was supposed to be right away when he heard us approaching for a high-angle identification pass."

"I was also scrambled on one mission to help a pair of US F-l0lA Voodoo fighters that had an emergency at high altitude above a very thick undercast. They joined up on each side of me and we let down through the cloud deck for a landing at Solingen AB in West Germany. (They sent us a box of whiskey, thank you very much!) Such was our life in EC-1/13 with the F-86Ks."

In April 1962, and EC 1/13 converting

in September. All remaining aircraft were consolidated into EC 3/13 at Colmar,

beginning in April 1962. The last 22 Amnie de l'Aire F-86Ks were returned

to Italy and sold to Central and South American nations that wanted a first

line interceptor to defend their skies against unwanted intruders.

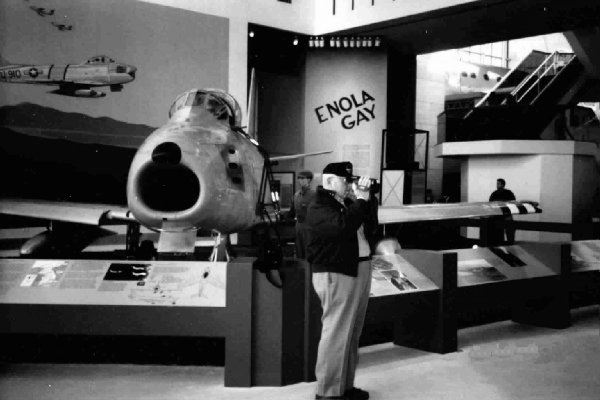

THE STORY BEHIND THE PHOTO

Association member Sam Jackson uses a video camera in front of the F-86 display in March 1997. Note sign pointing the way to the "Enola Gay" display. (Credit - Sam Jackson)

One of our members sent this photo along with a newspaper clipping about the

F-86 exhibit at the Smithsonian's Air & Space museum during the Air Force's

fiftieth birthday year. After studying the photo, it occurred to us that the

name "Enola Gay" in the background might confuse some of today's

young people. No, kids, that isn't the name of the Sabre. But there IS a connection

that might have been forgotten unless we printed the story. So here goes -

In early 1997, the photo above was sent to us by member Sam Jackson, of Centreville,

VA. Shortly thereafter, another member sent us a newspaper clipping about

the Air & Space "Sabre" exhibit. The clipping had a particularly

beautiful picture of the exhibit. Our President, Dee Harper, knew that the

photo would be perfect on the cover of SabreJet Classics, so he asked the

Board Chairman, Jim Campbell, to try to get us a copy. Jim was well placed

to get this done, since he was in the marketing business in Detroit and had

the right contacts. Jim called the museum and was told that there were no

more copies available and it would take three months to produce one. Jim said

he knew the business and it shouldn't take more than three days. And furthermore,

he might have to call on our favorite congressman, Sabre Pilot Sam Johnson

(R-Tx) to help us out. We got the photo in five days and it appeared on the

cover of SabreJet Classics, Vol.5 No.1, Spring 1997.

Turns out Sam had recently been selected by the Speaker of the House to be

a member of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution. Are you starting

see why we got the Sabre photo so quickly? You may be interested in our take

on why and how Sam Johnson became a Smithsonian Regent.

Before all this, in the mid-nineties, there was a huge flap about the proposed exhibit of the Enola Gay (which dropped the first nuclear bomb on Hiroshima) in the Smithsonian. Many WWII veterans and veterans' organizations opposed the exhibit on the grounds that it emphasized the casualties caused by the Enola Gay, and did not reflect adequately the positive side of the mission, which arguably saved millions of lives by bringing the war to a speedy end. Air Force magazine was a leader of this opposition, and the F-86 Sabre Pilots Association joined the fray with a flood of letters (on our letterhead) to both the Smithsonian and sympathetic Senators and Representatives of the U.S. Congress. Perhaps the most vocal (and credible) critic of the proposed exhibit was Sam Johnson, and the "good guys" won. Happy ending! The exhibit was changed for the better and Sam was appointed a regent of the Smithsonian Institution.

Congressman Sam Johnson and his lovely wife, Shirley, attended our 11th reunion in 1997 and Sam was the principal speaker at the banquet. (SabreJet Classics, Vol.5 No.2, Summer 1997).

So we think you'll agree that there

is quite a story behind the photo of the F-86 with an "Enola Gay"

sign hovering over it. The Sabre is no longer on display at the Air &

Space Museum, but we think it can be seen either at the Smithsonian's Garber

facility in Silver Hill, Md., or the new Dulles facility when it opens. By

the way, the "Enola Gay" sign refers to the entrance to that display,

which is just behind the Sabre.

The REST of the Story

JACQUELINE BRIAND

Without the heroism of Jacqueline Briand, the F-86 Sabre Pilots Association might be a very different organization, or might not exist at all. She played a big role in the survival of 2nd Lt. Flamm D. Harper, now a retired lieutenant colonel, and the distinguished Chairman of the Board-Emeritus of the Sabre Pilots Association.

"No. 1 SNAFU", the story of how Dee Harper was shot down, evaded, and was rescued in Korea was told in the Fall 1996 issue of SabreJet Classics. That was the second time Dee was shot down behind enemy lines and evaded capture to return to his unit. In so doing, he became one of only two American pilots known to accomplish this feat.

Dee was downed for the first time on 15 July 1944, while flying a P-38J on a fighter-bomber mission near the town of Montmorillion, in Occupied France, almost 100 miles south of Paris. This story was recounted in the Spring 1999 issue of The Daedalus Flyer, a publication of the Order of Daedalians (The National Fraternity of Professional Military Pilots). While flying the element lead in a flight of four Lightnings lead by First Lieutenant Robin Olds, Dee's aircraft was either hit by flak or flew through the debris of a bomb dropped by another flight member. With his aircraft severely damaged and at very low altitude, Dee rode it down to a wheels-up landing in a farmer's field. He swears he had very little to do with the successful landing, and calls it "miraculous".

As Dee crawled out of the wrecked P-38, he spotted a French girl standing alongside the meadow, and she beckoned him to follow her. Bloody, battered, and bruised, he followed the young lady to her grandparents' home, nearby. The family fed him and tended to his injuries, sheltered him overnight, and provided him with civilian clothes. Then her father assisted Dee in evading German troops, and young Lieutenant Harper was shortly placed in the hands of British SAS (Special Air Service) troopers and the French Maqui (fierce underground fighters). After a series of adventures with those folks, Dee finally made it back to England on 6 August 1944 via a behind-the-lines pick-up by an RAF Lockheed Hudson.

But it all began with the fourteen year old French girl, who had the courage to assist the American fighter pilot, and saved him from almost certain capture by German troops. Her actions and those of her family and the other French citizens who helped Dee Harper placed them at great risk if they were discovered. The Germans were well-known for severely punishing French people who aided the Allies.

Dee didn't learn the name of the French girl until 1998, when they were placed in touch with each other by a French archaeologist who was working at the site of Dee's crash. This began an exchange of correspondence between Dee and his rescuer, Jacqueline Briand. In October 1999, Jacqueline, now 70 and a great-grandmother, and her husband visited Dee at his home in Las Vegas. It was their first visit to the USA, and Dee arranged a marvelous itinerary of sightseeing and partying for the Briands. The event was covered in grand fashion by the Las Vegas Review-Journal on 1 November 1999.

The F-86 Sabre Pilots Association

sends its sincere thanks to Jacqueline Briand for her heroic actions, which

helped Dee Harper survive to fight another day and to lead our great association

in the last decade of the Twentieth Century.

FIRST FLIGHT SURPRISE

(A Dog of a Checkout)

By Jim Hancock

In October 1956, fresh out of pilot

training and sporting a shiny new "brown bar", I began my rated

flying career as a T-33 Instrument Instructor Pilot with the 3558th Combat

Crew Training Squadron, Advanced Interceptor, at Perrin AFB, Texas. Major

Gus Sonderman was the Commander. Two years later, it was time for me to upgrade

to the F-86D/L as an All-Weather Interceptor IP. My checkout Instructor Pilot

would be Captain A. D. Stanley.

The checkout consisted of ground school, simulator, and flying training. Simulator

training focused on aircraft performance, emergency procedures, airborne intercept

tactics, emergency procedures, emergency procedures and more emergency procedures!

About twenty hours worth, as I recall. Lots of sweat was generated in the

"box". Finally, having passed my "sim check" early one

morning, I was scheduled for my first flight later that day. It would not

be a dual ride. A. D. would chase me.

"Sabre flight of two, cleared for takeoff." Into position, Brakes SET, Power FULL MILITARY, Engine/flight instruments CHECKED, Blood pressure/heart rate MAXED, Light the burner, check nozzles OPEN, EGT, RPM and Fuel flow STABILIZED, Brakes RELEASE and AWAY WE GO! I could almost hear and feel the vacuum tubes in that "state of the art" electronic fuel control as they tried to optimize performance in that big J-47. Outside, I knew, the whole base could hear the roar. What a blast! Man, was I pumped! My IP, A.D. Stanley, rolled three seconds later.

At just about rotate speed (we didn't use Vr in those days) I began to feel and hear power surges accompanied by fuel flow and nozzle fluctuations. (This isn't really happening. I'm still in the simulator - right?) "SABRE LEAD ABORTING!" Throttle CUT-OFF, Speed brakes OUT, Drag chute DEPLOY, Drop tanks JETTISON (?), Brakes AS REQUIRED. Just like the book said. The tanks rolled to the right, fortunately, as A. D. was coming up fast on my left. Naturally, the tanks ignited, resulting in a rather spectacular infield fire which caused the Runway Safety Unit (RSU) crew to evacuate and the airdrome was subsequently closed. My Dog and I came to a screeching halt at about the 2,000 ft. mark of the 8000 foot runway.

Needless to say, there was considerable "Monday morning quarterbacking" about that one. I was feeling a little sheepish, yet I knew I had correctly followed the procedures that had been drilled into my head. I must have related the incident a dozen times; to A. D., to Flying Safety, to Maintenance, (they did confirm a fuel control malfunction), my Squadron CO, Group CO, Wing CO, and Lord knows who else. However, all concurred that I had responded properly to the situation, but maybe I was a little too aggressive. Had I more experience in the jet, I probably wouldn't have "punched" the tanks off? Twenty-twenty hind sight. It's great!

The next morning A. D. and I finally

accomplished my initial checkout flight and I went on to instruct in the "Dog"

for another two years. Eventually our squadron converted to the F-102 and

guess who checked me out in the "Deuce"? A. D., of course. This

transition went as advertised, but, A. D. did cut me a little slack when he

chased my first flight. Six seconds this time.

Sabre Squadrons

56th FIGHTER SQUADRON

"WORLD'S FINEST

from Henry Head

The 56th FIS evolved from the 56th

Pursuit Squadron, a unit within the 54th Pursuit Group, at Hamilton Field,

California. The 56th PS was activated on 15 January 1941, defending the war

industry in Southern California until June 1942. On 20 June 1942, the 56th

(now) Fighter Squadron, took their Bell P-39 Airacobras to Nome, Aaska, where

they won a Distinguished Unit Citation for operations against the Japanese

in November 1942. In 1943, the 56th FS returned to the ConUS, and were based

at Bartow Army Air Field, Florida, where they converted to North American

P-51 Mustangs. One year later, on 1 May 1944, the 56th FS was disbanded.

Re-constituted and activated at Seifridge AFB, Michigan in November 1952,

the 56th (now) Fighter Interceptor Squadron was assigned to the 4708th Air

Defense Wing, and equipped with North American F-86F Sabres. In February 1953,

the 56th FIS began conversion to F-86D interceptors, and was assigned to the

575th Air Defense Group.

On 18 August 1955, under Project ARROW, the 56th FIS designation was transferred from Selfridge AFB to Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio, initially under operational control of the 4706th Air Defense Wing, then the 58th Air Division(Air Defense) on 1 March 1956, where the squadron was the primary air defense unit for southwestern Ohio and the research facilities at Wright-Patterson.

In the Spring of 1957, the 56th FIS began re-equipping with the North American F-86L Sabre, an improved version of the F-86D which incorporated the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment system, or SAGE. The unit, commanded by Lt.Col. Harad 'Axe' Askelman, became proficient with both the F-86L and SAGE, and won an Air Defense Command "A" award for live rocket SURE-FIRE missions in the late summer of 1957.

The transition into the F-86L was

short-lived however, as the squadron began transition into the "missile-witha-man-in-it",

the Lockheed F-104A in May 1958. The 56th FIS was now under operational control

of 30th Air Division (Air Defense), before being transferred to the Detroit

Air Defense Sector in April 1959.The 56th FIS was deactivated at Wright-Patterson

on 1 March 1960.

Memories Of Great Fighter Pilots

FREDERICK C. "BOOTS" BLESSE

by Earl Brown

As with most great men and women of history, stories abound which shed light

on the source of their greatness. With this in mind, SabreJet Classics presents

the second in a series of anecdotes received from you, our members. Lt. Gen.

William E. Brown, USAF (Ret), of Alexandria, Virginia, sent us the following

story. We invite other members to send their memories of the great ones they

have known.

I was a 24 year old 2nd Lt when I met Capt. Blesse. We were in the 334th FIS,

4th FIW, at K-14 (Kimpo), ROK, and flying F-86 Sabres into North Korea looking

for MiGs.

Boots was clearly the best pilot in our squadron and probably the best in

the wing. Not only could he fly and fight in the Sabre, he could tell others

how to do it.

He was also the natural leader of the squadron. I had the impression that if we were all on a Desert Island with no visible signs of military rank, Boots would still be the leader. He used to say that "Rank is your ace in the hole. Don't use it until it is necessary."

He led by example. He was a ferocious competitor. In every game he played, he refused to lose. An exceptional fighter pilot needs the same skills as a superb athlete.

First, start with DESIRE TO BE IN THE GAME. Many people trail to be fighter pilots, but not all will fly to the sound of the guns. Boots was always listening for the sound of the guns and would go uncommanded to that sound. Like Michael Jordan, when the game was on the line, he wanted the ball.

Second, hand-eye coordination and physical strength and stamina are absolute requirements. I try to tell my civilian friends that there can never be old men flying actively as fighter pilots. The physical demands are too great. Strap on the oxygen mask for an hour and a half, maneuver to pull Gs that magnify your body weight by 4, 5 or 6 times, maintain awareness of the situation around you in 3 dimensions, anticipate your enemy's moves, plan your own moves, fly the airplane within its prescribed limits of airspeed, altitude, engine temperatures, and do these things continuously during the flight. Boots did all of these things exceedingly well.

Third, calculate and think about the tactics of the engagement between two fighter planes. Scheme about ways to maximize your airplane's advantages and zero in on the opponent's weaknesses. Boots had thought about the problem of air-to-air combat for many years. He had trained and practiced and honed and polished tactics for years.

I have been told that he has been an excellent golfer for many years. The skills he learned in observing the effects of tiny changes in the angle of the club head and velocity of the swing translated almost directly into the sensitive handling of the Sabre at the limits of its flying envelope, when the aircraft is very close to stall at high altitude or when you are turning as hard as you can at maximum speed at low altitude. Most fighter pilots could fly the Sabre well in the heart of the envelope defined by maximum and minimum speeds and maximum altitudes. Only a few could get top performance from the plane while flying near or at the limits of the airplane's normal envelope.

Boots delighted in taking young pilots up and showing them how to fly at the edges of the airplane's capability. There was a mission when he shot down a YAK-9, a Soviet fighter that looked like a cross between a P-47 and a FW-190.

Col. Royal Baker, the group commander, had engaged two YAKs and was attacking them. As he closed into firing range, the YAKs would pull into a tight turn and evade his bullets. Boots heard the melee on the radio and we flew to the fight location. Boots set up an orbit high above the fracas and watched Col. Baker make two or three passes. Each time the YAKs would simply out-turn him as he reached firing range. Finally, Boots asked if he could make a pass and the frustrated Col. Baker approved. Boots started down on the classic high-side approach, just as though he were on a towed target. As he slid into range, the YAK almost casually, racked up into a hard turn, surely thinking "Another dumb American!" Was he surprised when instead of over-shooting and zooming up for a re-attack as Col. Baker had done, Boots popped the speed brakes on the Sabre and slowed to just a mite faster than the YAK! He continued to close and could now match the turning capability of the propeller plane and just hosed bullets into the fuselage. The YAK went down.

This maneuver is one that Boots had used in training against P-51s and he knew from experience that it could work, especially if the prop plane pilot was not expecting it. The danger was that, once he had the speed brakes out and slowed down, he only had one pass to make the kill. His Sabre could not accelerate as fast as the prop plane and if he missed, he would be a sitting duck for the enemy pilot. But he knew that he would not miss. He had done this before in training and had the film to prove it.

In 1970, I think it was, Boots was commander of George AFB and a one star general. The mission of the base was F-4 replacement training. The general came down to the squadrons and flew to the gunnery range as a member of the training flights. It was a custom for each flight member to put up a quarter for each event and the high scorer in that event won the quarters. Usually if a higher ranking officer flew and won the quarters he would turn them back to the young officers. Boots always won and ...he always kept the quarters!

I'll always remember Boots Blesse as a competitor, a winner, and a leader. He had the guts, and he deserves the glory!

Editor: Retired Major General "Boots" Blesse is a member of the F-86 Sabre Pilots Association, and lives in Melbourne, Florida. A Korean War ace, he was credited with ten kills. His famous book, "No Guts, No Glory", is legendary among fighter pilots.