MAJOR GENERAL JOHN C. GIRAUDO

A True Fighter Pilot Leader

Not every fighter pilot is a leader. Not every leader makes a good commander.

Not every commander has the compassion to inspire the men in his command to

excel in their endeavors. Not every combat commander can or has the guts to

lead by example. But JOHN C. GIRAUDO, 'The Big Kahuna", could and did!

In my mind, he was the epitome of a true fighter pilot leader.

I've had the good fortune to serve under several commanders whose input to my career helped me achieve some degree of success. I've fondly referred to those few as 'Boss'. One such was when I was assigned as an instructor pilot in the Fighter Weapons School in the mid-1950s. The school was commanded by Lt. Colonel Giraudo, and he became my 'Boss'. That super experience was the beginning of a long-lasting friendship and respect for one of the United States Air Force's better fighter pilots I have known.

At that period in time, this stellar individual had already completed a career that would rival anything that could be fantasized by the Hollywood script writers. He had come from rock hard stock in Santa Barbera, and had already answered the call to defend our country in two wars. He had become a POW in WW2, but not before flying more than his share of combat missions. After repatriation, he was one of two Air Force officers who served on the staff of General Dwight D. Eisenhower during the formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a major diplomatic task that aided the recovery of our Free World allies.

He returned to Tyndall where on an earlier assignment, he had assisted in developing the first jet all-weather instrument flying program for the T33. But Korea had become a problem and he volunteered for his second combat tour. In Korea, he was shot down on his 99th mission (100 was the tour). His confinement by the North Koreans gave him first hand knowledge of the oriental mind as an adversary.

After release from confinement, he took command of the Fighter Weapons School at Nellis where he was instrumental in bringing it into prominence. In 1956, he went to the Hawaii ANG as the Senior Air Force Advisor. In 1957 that unit was selected as the most operationally ready Air Guard fighter unit in the United States. Follow-on assignements from Hawaii included Joint Staff, National War College, and wing command positions in Ubya and Europe.

Then came the Vietnam War. As many of us know, the air war North was a test of guts against some of the most deadly defenses even seen in modern aerial warfare. into this conflict goes a leader of men with the ability to get an impossible task accomplished, despite the odds. What would you have thought about going into the lion's den a third time, when the past had produced more misery than one man is entitled to? John Giraudo didn't flinch. He didn't like it, but he was there when it counted. I have to talked to many individuals who served in the 355th Tactical Fighter Wing when Colonel Giraudo was the commander, and to a man, not one of them would have wanted to be under the command of a more respected, responsible, and capable officer. I personally believe it was his finest hour, because he and a few others of his calibre proved what true leadership ability can accomplish during a less than ideal cause.

After 100 missions, he was on his way to bigger and better things. He had beaten the monkey of that 99th mission. Not many of us would want the chance to prove such a point. John did it in his magnificant stride, the stride of a reluctant hero. And yes, he was a hero by any standard you would want to use as a measure. He went on to get his star, which he so richly deserved.

Flag rank brought him back to Washington and five years in Legislative Liason in the Office of the Secretary of the Air Force. The last three years were as Director where he earned his second star. Those three years saw a higher level of cooperation between Congress and the USAF than ever before. It was then back to the field as Commander of 17th Air Force, which comprised all US tactical air units in Central Europe. He returned to Florida in 1975 to become the Director, Plans and Policy, J-5, at Headquarters, United States Readiness Command at MacDill.

I had the pleasure of making contact with him from time to time during the early 1970s, and it was always a boost for my morale. His positive attitude was like a tonic to all who believed in good people getting the job accomplished in the best possible way, despite interference from less dedicated individuals. P> In 1977, the year General Giraudo retired, I took command of 17th Air Force. He had been the commander only a few years before. It was first hand knowledge for me on just how much his influence had impacted on this front line organization. A good commander leaves an indelible mark, John Giraudc was there to see. It was a priviledge for me to ha my name on the same list of commanders as his.

1 had the occasion to be in contact with John Giraudo several months before his death. He gave me some help on some stories I was trying to publish and we exchanged letters a few times. He told me of his 'Opus', the Bio he started in 1985 and finished in 1993 for the Air Force's Historical Center. (It well worth reading if you ever get the chance.) He explained it to me saying, "I probably treat some people you know, and who niay be your friends unfriendly. But in more cases I praise highly the many I served with over thirty five and a half years. It's a great family, with just a few bastard children" To me that explains the man. He knew we had a few clinkers in our midst, but he could take the good the bad, and the indifferent, and make them into the best. He had the ability and the charisma to do it all.

I would like to share a portion of my last letter him. It portrays my feelings and I think the feelin of many - "Boss, I want to thank you for the major contribution you made to my life and career in the Air Force. I am just sorry the time was so short there at Nellis, when I had the opportunity observe a real 'Fighter Pilot Leader'. I will always be extremely proud to say I know John Giraudo, one of the best leaders I have ever known."

We, who have served in the United States Air Force have been blessed with some great leaders in I past and I'm sure the future will bring on more. I when the final role is called, none will stand taller than John C. Giraudo. We were fortunate to have him on our side.

DAN DRUEN

NO. 1 SNAFU

by Dee Harper

June 28, 1953. It started as did almost every other day during the closing

months of the Korean War at K-55--BUSY! At the 18th Fighter Bomber Group (FBG)

Combat Operations Center, we were in the final stages of planning a strike

against a railroad bridge located on the Haeju peninsula. Suddenly, the scream

of an F-86 riding the Mach broke the quiet of the office. Someone had made

a low altitude pass over the base. We walked outside to see what was happening.

I soon determined it was Howard "Ebe" Ebersole returning from his

100th mission. In his exuberance, he put on a great flying exhibition, but

one highly frowned upon by the Powers That Be. Colonel "Marty" Martin,

the 18th FBG Commander, jumped into his jeep and headed for the flightline.

He returned shortly to continue the flight planning. Little did I realize

that a chain of events had started that would have a major impact upon my

life for the next several months. A chain of events for which Ebe will eternally

be indebted to me.

Meanwhile, the mission we were planning was a skip bomb strike by four aircraft as part of a special project assigned to the 18th Fighter Bomber Wing. Because we were the first USAF wing to be assigned F-86F-35 aircraft equipped with hardpoints for ordnance loads (a new mission for the Sabre), we were tasked to conduct "The USAF Suitability Test of the F-86 Aircraft as a Fighter Bomber". This was to be done under combat conditions, which was very unusual. The logical choice of project officer for these tests was the 18th FBG Operations Officer, so that job fell into my lap. Missions scheduled to meet project requirements required obtaining both pre-strike and post-strike photography. Fifth Air Force then determined the impact points of all ordnance delivered in order to compute the accuracy. These data, along with "type of delivery", "ordnance used", etc., were then forwarded to Wright Patterson AFB by Fifth.

Bob Hoover, the North American Aviation company test pilot, had been on base for several days to brief our pilots on the flight characteristics of F-86F-35 equipped with the 6x3 solid leading edge wing and to give a flight demonstration. Everyone figured it would be good for Bob to see a little more combat action and Bob was eager to go. The previous day he had flown a dive bomb mission. Living up to his reputation, he had scored a direct hit on a bridge. The skip bomb mission scheduled today was going into a relatively safe area. Hoover was scheduled again to fly number two position on the mission leader, Colonel Marty Martin. Lt. Col. Harry Evans, 12th Squadron Commander, and the operations officer, Ebe Ebersole, filled out the flight as numbers 3 and 4, respectively. How much power could you put into one mission involving four aircraft, particularly a milk run into the Haeju Peninsula? Little did anyone realize that this mission would end as a perfect example of the term SNAFU.

As Ebe walked into the Combat Ops Center where Colonel Martin, Lt. Col. Evans and Bob Hoover were already discussing the forthcoming mission, Ebe said, "Colonel Martin, I'm scheduled to fly this mission with you." Colonel Martin then informed him in no uncertain terms that he was grounded, and ended the discussion by stating, "Dee is flying in your position". I was in full agreement. I had had a tough day at the office - a day that had started early when I met the Fifth Air Force courier flight to pick up our frag order. I looked forward to getting out of the ops center and flying. This was to be a milk run, but a very interesting mission. It was one that I had planned and now I was to be in on its execution. The river banks were quite prominent so it appeared we could plant the bombs in the river bank at both ends of the bridge and drop the whole span. I was looking forward to this show.

Even a raw recruit knows it is bad policy to volunteer for anything in the military. I had also learned during WWII that flying on a mission as a spare or being substituted on a mission was bad news. On my last combat mission in a P-38 during World War II, acting as the squadron spare, I joined up with 1/Lt Robin Olds' flight as number three man. While strafing an ammo dump, I flew through a major explosion that demolished my aircraft in mid-air. Even the bullet-proof windscreen had been scraped off the fuselage and my leather helmet ripped away as I flew through the debris. I made a crash landing in south central France without any visual reference to the ground. My vision was impaired by (1) the slipstream, (2) smoke coming through the heating system from the burning right engine, and (3) blood flowing from scalp wounds. I just rode it out until I hit something and stopped. No talent was involved in that landing! It took me 22 days to return to my outfit. Now, here I was in Korea, and even with this background, no warning bells went off. I had no idea that the on-the-job-training (OJT) gained from my MIA experience in Europe would be fully tested before this day was over. It was to be a long, long day!

As we arrived over the target we went into trail formation. Each aircraft made individual attacks, from around the clock, with sufficient time between attacks for the delayed fuses to detonate before the next aircraft came in. This tactic seemed safe enough since there were no known enemy defenses within the area. I was the last aircraft to make an attack. All of our bombs (which should have skipped, remember) plowed into the soft silt of the river bank (not apparent from the photography) and exploded several thousand feet from the target. As I came off the target I stayed low until a short distance from the target area and then started a shallow, climbing left turn at well over 400 knots. I passed over a small marshaling yard with a few box cars in it, and noticed some tracers from a quad 23mm gun curling up towards me. The troops on that gun had received a good checkout. Every round that missed was out in front of me.

I heard two dull clanks in the front of the aircraft and pulled up to about 7,000 feet to check out my bird. Everything appeared completely normal. About that time, Harry Evans had picked up the box cars in the marshaling yards. It was decided to hit them before we departed. I had a lot of respect for the gunners on that quad gun, and I knew it had to be neutralized. I knew right where it was, and I was in a perfect position to make an immediate attack. I pressed in and knocked out the gun while the rest of the flight shot up the box cars with no observable results. With that we started a climb to cruise altitude enroute to K-55.

At about 16,000 feet I noticed a high frequency vibration in the front end of the aircraft. I advised the leader of my problem, reduced power and leveled off. The others in the flight began to close in on me. About this time the engine compressor exploded. The throttle was ripped out of my hand to the idle position, and the flaps went to the full down position. Fortunately, the flaps retracted when I hit the switch. I moved the throttle to the shut off position , turned the fuel tanks off, and set up a glide to the west hoping to make the coastline before bailing out. Harry Evans slid in on my wing and said, "Dee, check that your fuel is off. You have about 200 feet of flame following you." I rechecked the fuel switches and insured that the throttle had been stop-cocked. Everything was off! The necessary "Mayday" calls were made and an SA-16 air-sea rescue aircraft was moving into position to meet me at the coastline. About 10 miles from the coast, Harry called and said, "Dee, you had better get out. You look like a roman candle." There was no smoke or heat in the cockpit and I could not see the flames. I decided to ride it out until I made the water, where the chance of rescue would greatly improve. With about 5 miles to go, a second explosion occurred. This one really shook me around in the cockpit. No one had to tell me about the fire now. Sheets of fire were coming from both the wing trailing edges and the cockpit was filling with smoke. I decided it was time to go. I could walk the remaining few of miles.

I positioned myself in the ejection seat and blew the canopy. The bang from the canopy charge startled me so much, I froze! Then I realized the noise came from the canopy's explosive charge. I squeezed the seat trigger, ejected, and made a free fall from about eight thousand feet to avoid being spotted by anyone on the ground. I tended to fall head first and on my back at about a 135 degree angle. When I'd look around to see the ground, I'd start to tumble. I'd clamp my feet and arms together and again end up on my back. The last time I looked around, I could see the leaves in the trees. I pulled the rip cord in sheer panic! My chute just blossomed and then collapsed as I made contact with the side of a rocky cliff and plunged into boulders at the foot of the cliff. It was in the evening so I had a land breeze pushing me directly backwards. I ended up catching a large oval shaped boulder right in the middle of my back. The impact completely paralyzed me. All I could think of was, "What a hell of a way to die - draped over a boulder in a North Korean canyon".

The decision to bailout before making the Yellow Sea was the right one. A third explosion occurred before my aircraft crashed on the other side of a high ridge just north of me. A sad ending for Sabre #52-4312. Harry Evans lost track of me after the bail out and asked if anyone had seen my chute. Colonel Martin told Harry that my chute had opened momentarily and then collapsed. He pointed out the canyon where I was located. By this time, everyone in the flight was low on fuel. In spite of this, Harry made a low pass down the canyon to determine my exact position. I could see him coming, but I was completely paralyzed. The only things I could move as he flew past were my eyeballs.

At this point, low fuel forced everyone to leave. Colonel Martin and Bob Hoover headed home. Harry Evans headed for the Korean Island of P-Y-DO (Paen Gu Ong Do in Korean) located north of the 38th parallel in the Yellow Sea. (For those of you who picked up Robert F. Dorr's book, "F-86 Sabre" at our '94 Reunion, there is a great picture of the beach at P-Y-DO on the inside of the front fly sheet.) Harry flamed out enroute and had to deadstick his aircraft onto the beach beside a cliff. He accomplished the landing without putting a mark on the aircraft, once again exhibiting his outstanding abilities as a pilot.

(If you didn't know Harry Evans, he was later the leader of the Sky Blazers, a USAFE F-84G acrobatic team that performed in Europe for several years prior to USAF designating the Thunderbirds as its official acrobatic team. Once, when overcome by some young pilot's story in a bull session, Harry remarked, "Son, I have more time in the top of a loop than you have total flying time." He was probably right.)

Colonel Martin's low fuel state forced him to land at K-14. Bob Hoover realized the seriousness of the situation (he was north of the bomb line against orders), and had been more conscientious about conserving fuel. He was the only member of the flight to return to K-55.

Only those airmen who have been downed in enemy territory truly understand the full meaning of the word "LONELY"! The feeling is so intense that it often immobilizes an individual. While evading in Europe, I remember every time I came to a bend in the road, I was sure there was a whole division of enemy troops lined up with every gun aimed at me. At the very least, this frame of mind is very intimidating.

From my European evasion OJT, I knew that my actions in the next 24 hours might very well determine the outcome of my current predicament. Within 12 hours of my crash landing in Europe, I joined up with a detachment of the British 1st Division, Special Air Service. Many members of the detachment had been dropped into enemy territory on several occasions. They were experienced experts on escape and evasion. All stressed the importance of immediate, bold action. During the first 24 hours, there will usually be several opportunities for escape. You have to be alert to these opportunities.

Without this experience in Europe, I doubt very much that I would have had the mental toughness to take the actions necessary to recover from my Korean problems.

Back to the Haeju Peninsula. After several minutes the paralysis had worn off and I rolled from the boulder. As a minimum, I knew I had quite a few broken ribs but the adrenaline was really flowing. I was again ready for action, and apparently, no one had spotted me during the jump. I had already been given my first big break! All action by the enemy appeared to be on the other side of the hill where the aircraft had impacted. I quickly hid my parachute, but kept the dinghy and started for the coast. I wanted to get into a position where I could plot a course to the sea before dark. Events permitting, I intended to be in my dinghy paddling out to sea before sunrise.

After traveling about a half mile, a flight of F-84Gs arrived on the scene - everything was looking up! They immediately began to make passes over the wreckage of my aircraft attempting to locate me. Fortunately, the base leg for their passes was right over the top of me. I grabbed for my emergency radio and attempted to contact them. No luck! I had survived the hard landing, but the radio was dead. The only remaining signaling device was my parachute.

I headed back to the chute as fast as I could move. As I approached its location, I could hear Chinese or Korean voices. I moved in slowly. Two North Korean soldiers had located my chute. I knew the "rescap" was in place, and this meant that probably a helicopter was nearby. I decided to go for broke! I pulled my .45 pistol and started to move in slowly. I'd always had a problem qualifying with the Colt .45, so I knew that I had to get in close. The odds were two to one. This was no time to miss. When I got into position, I shot the two soldiers and gathered in my chute. Realizing that time was of the essence and my shots would attract a lot of attention, I ran to a nearby clearing and spread my chute on the ground. I then sat down in the center of it, and was spotted by the very first F-84 to pull up over me. He reversed his turn and made a pass directly above. I could now hear enemy activity all around. Shortly thereafter, a helicopter popped over the hill - certainly the most beautiful bird I had ever seen.

The F-84s did a great job of pinning down the enemy. The chopper moved over me and dropped its sling. When I was in the sling, the pilot quickly pulled up to about 3,000 feet to get out of the line of fire. Then I was reeled in. I noticed a movie camera attached to the cable boom taking pictures of my rescue. The corpsman was not in position to help bring me aboard when I was level with the door to the cabin. He was busy running the camera. Hanging there in mid-air, I decided I could get aboard myself. Even though my finger tips could barely touch the edges of the door, I yanked myself into the cabin onto my feet. Boy, adrenalin can work wonders!

The pilot inquired if I was OK, and I answered, "I have a few broken ribs, but OK." He then asked if it was all right if he returned to Chodo Island to refuel - there were still combat missions north of the Han River and this was the only chopper in position for rescue. He would drop me off at K-16 the next morning. At this point, I was agreeable to anything!!! As we headed toward the island, I stood at the cabin door watching Korea slide away beneath us. Shortly, I began to feel pretty rocky. The adrenalin had stopped flowing! I looked at the opened stretcher on the cabin floor. It looked pretty good so I lay down. It took 4 men to get that stretcher out of the cabin after we landed at the island. I could not make it back to my feet.

I was almost completely immobile, and couldn't move from a prone to a standing position or vice versa. But if I held my body stiff, two men could move me into either a standing or prone position. Twice during the night the radar site and chopper pad on the island underwent bombing attacks. The bombing was erratic but it did necessitate evacuating our bunks and retiring to a nearby hillside where tunnels had been dug. Each tunnel was just big enough for one man. Everyone selected his own tunnel and crawled in. In my physical condition, it was like trying to crawl into a gopher hole. I later was diagnosed with broken ribs and severe contusions to the spinal column. The latter injury still gives me problems.

In the morning, the helicopter delivered me to the Army MASH Unit in Seoul, and the following day Colonel Martin paid me a visit. I asked that he get me transferred to the hospital at K-55. I didn't realize that I had flown my last combat mission. The Korean War ended July 27, 1953. I was not back on flying status until August 28, 1953.

The film taken during my rescue was broadcast on all national TV networks about four days later. Not the best way for your family to be notified of your latest escapades.

I have a letter from the USAF Escape

& Evasion Society which confirms that I am probably the only living airman

who has successfully evaded the enemy in two different wars. Not a record

that one strives to achieve! Lucky, or Unlucky? You call it. Ebe, you owe

me a few drinks for this one. I'll collect at our next reunion.

EDWARD J. HORKEY

NORTH AMERICAN AVIATION

Without Ed Horkey and the work he did at North American Aviation, Inc., it

is likely that many of us would not have enjoyed so many thousands of hours

in the F-86 Sabre, as well as the T-6 Texan, P-S 1 Mustang, F-82 Twin Mustang,

B-45 Tornado, and F-100 Super Sabre.

Born in 1916, Ed graduated from the California Institute of Technology with advanced degrees in mechanical and aeronautical engineering. He began working at the Guggenheim Aeronautical Wind Tunnel, then went with North American in 1938. There he was active in such fields as aerodynamics, thermodynamics, and wind tunnel and flight testing. In all, he spent fifty nine years in aerospace and related technologies.

He had a giant impact on North American aircraft, and probably will best be remembered for his leadership in developing the laminar flow airfoil (a major reason for the success of the P-51), and the "all-flying tail" used on all models of the F-86 except for the "A". The "all-flying tail", more than any other single feature, may well have provided the Sabre pilot with the margin needed to defeat the MiG-1 5 in the skies over Korea.

Ed's many contributions included the manufacture and sale of drop tanks, pylons and ejection mechanisms, connectors, and plastics. He held several patents and had patents pending. In later years at North American, he worked in the Space Division as Director of Apollo Ground Support Equipment.

Ed believed in personal contact and observation of the military customers who used North American equipment. He made many trips to organizations in the field, to see first hand what the problems were. One of these trips was to Korea with the first shipment of F-86Es. He was accompanied by George Welch, the legendary North American Chief Engineering Test Pilot at that time. After watching the Sabre operations at K-13 (Suwon), he was heard to remark, "I never realized we built the F-86 to be used like this!" He was particularily impressed with the 5000x200 foot runway with no taxi strips, requiring the returning Sabres to land on one side of the runway and taxi back on the opposite side as other Sabres were landing.

Ed Horkey also visited the USS Midway during the Carrier tests of the XFJ-2 Fury, which was essentially a modified F-86E. He wanted to see how the Fury stacked up against the Grumman F9F-6 Cougar and Vought F7U-3 Cutlass.

In "retirement", Ed could always be found at the Reno National Air Race, and at the EAA gatherings at Oshkosh - and always near his beloved P-51 Mustangs.

Most recently, Sabre pilots will remember that Ed was the principal speaker at the Sabrejet dedication in Freedom Park at Nellis AFB, duridg the 9th Reunion of the Sabre Pilots Association. At that time, Ed reviewed how the F-86 was born, and he made one fact very clear - the F-86 Sabres that flew in Korea were the key to preventing a Chinese Communist victory in 1953.

In August 1996, the North American Aircraft Division's annual reunion honored the F-86 Sabre. Held at the Santa Maria (CA) Museum of Flight, the event also honored Ed Horkey for his contribution to the F-86 program. A fund was established in Ed's name, and it was agreed to dedicate his technical papers, writings, and memorabilia as part of a new wing of the Museum of Flight. Sadly for all of us, Ed Horkey was not present. This renowned engineer and friend of fighter pilots iiiiiin general, and Sabre pilots in particular, died on 28July 1996. He will be missed, but never forgotten for his memory will be seen in every flying F-86 ar P-51; and forever in photographs of those great machines. THANKS ED!

Editor's note; Our thanks to Association

member John Henderson (Mr. Sabre Tech Rep" to many of our members), a

close friend of Ed Horkey for providing this account of his many achievements.

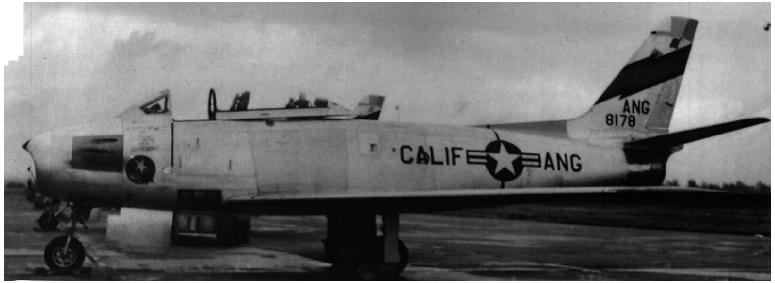

OL' 178 was assigned to the 196th FIS/California ANG at Ontario ANG Base in 1955. An F-86A-5, the Sabre had flown with the 1st FIG during 1950, before going to Korea with the 4th FIG later that year. Capt. Archi Nogle flew OL' 178 on her final Air Force flight in 1961.

LOOKING BACK

by Archie Nogle

As the jet engine revved up on

the tarmac of the old RAF base at Duxford, Englaud, I could have closed my

eyes and turned the clock back to 1953, when the hair wasn't grey and the

body was a little trimmer and firmer. And it was I that was climbing into

the cockpit, ready to soar into an incredibly blue sky with puffy, floating,

whiter than white clouds for another mission.

My fascination with flying went through the model airplane phase, wanting

to fly the real thing, then being able to fulfill that dream in 1943 when

I joined the Army Air Corps. I went to flying school and after seemingly endless

classes and months of schooling, had the wings of an Army Air Corps 2nd Lieutenant

pinned on me. It was the proudest day of my life.

At the end of WW2 I left the service to continue my education at Whittier College. Not wanting to end the thrill of flying, I joined a local reserve squadron. At the end of 1952, the (now) US Air Force recalled me to active duty, and beyond my wildest hopes, assigned me to the 63rd FIS at Oscoda, Michigan, flying the Air Force's best, the F-86F. I went through a two month refresher course at Maldon, Missouri, reporting to Oscoda in March 1953.1 had six flights in the T-Bird, and was ready to suit up for my first Sabre flight. No words can express the moments of exhilaration, fright, wonder, and awe that I felt in the next couple of hours as I raced around the wild blue yonder of Michigan skies.

I was blessed to be stationed at Oscoda, as I met and flew with the worlds best Sabre pilots. The training I received was the finest to prepare me for the combat I would soon see in KoreA. What a priviledge to know the likes of Major Bill Shaeffer, my squadron CO (3 1/2 MiGs), Capt. Ralph 'Hoot' Gibson (3rd jet ace in Korea), Colonels Joe Vaughn and Claude Bird, and others too numerous to mention here. Most had just returned from combat in Korea.

The know-how these pilots imparted to me in those months made it possible for me to complete my tour with the 35th FBS/8th FBG at K-13, Suwon, Korea I would be remiss if I didn't mention Colonel Bobby Dawson, a great pilot and friend and my CO in Korea, Colonel 'Woody' Wilmot the 8th Group CO, Bob Donahue, Bob Lilljedahl, Jim Mclnerney, Bob Fulton, Bud Laury, Bob Hafner, and Jack Swigert.

One afternoon in late 1992 1 received a call from a man who identified himself as Duncan Curtis, a reporter for WARBIRDS WORLDWIDE, an international magazine. He said that in the preparation of the coming edition on the North American Sabre, they were tracing the history of one particular F-86A, 48-178. It had been purchased by Golden Apple Trust, Ltd. in the United Kingdom. "Was I the Captain Archie Nogle, the last pilot assigned to this aircraft? And did I fly her on the last flight to Fresno?"

I assured him that it was indeed my old aircraft, and that I had made that unflattering last flight. He then asked if I could send him any information, including pictures, etc, pertaining to the aircraft. I could and DID!

My material was included in the May 1993 issue, which was dedicated to the Sabre. This particular F-86A, 48-178, had been restored to its Korean Conflict markings, and was to be flown in an up~oming air show in Britain.

In September 1994 I was asked to be present as a guest of Golden Apple Trust and its President, Mr. Robert Home, and its pilot Mark Hanna, a former RAF pilot at the Duxford Family Air Show.

It was also the Gathering Of Eagles for 1994. Brig.Gen. Robin Olds, who had also flown -178 in 1950, was a guest at the air show along with many other famous pilots from WW1, WW2, and Korea. There were many aircraft types scheduled to fly. And when my old Sabre performed on Sunday, I was asked to narrate the flight during the 30 minute show for some 35,000 spectators, who had come from near and far on this beautiful day.

It was a dream come true and surely the highlight of the trip for this 'old fighter pilot'. I really wanted to fly 'Ol -178' again, but the memories of past years had to suffice on this day. But it was a great experience to see old 48-178 flying again.

Thinking back to my Oscoda days, I will forever be indebted to Bill Shaeffer who went to bat for me when the Air Force was going to change my assignment out of fighters. He made it possible for me to stay. Being the new kid on the block, I wanted to make the best impression I could. One day while sitting alert in the hangar at the end of the runway, the scramble phone rang and I answered "This is the hot pilot on the alert line."

There was a moment of silence on the other end and then the voice said, "And just what hot pilot am I speaking to?" Of course it was Major Shaeffer. I then realized that I should have said "This is the alert pilot on the hot line." I then identified myself, knowing I had really blown it. But he just laughed.

After rotating back to the States in 1956 I joined the 196th FIS/California ANG at Ontario, California. This is where I was assigned to F-86A 48-178. Again I flew with some of the Air Force's finest including Colonel Bob Love, Korean jet ace, Colonel Don Frisbie CO of the 196th, Group Commander Colonel Arthur Bridge, GE Test Pilot Whitey van Salter, Ryan Test Pilot Lou Everet, George Uvesey, Colonel Lloyd Hutton, and test pilot Ken Viktor.

In 1961 I delivered 48-178 to the 'bone yard', an aircraft mechanic's school at Fresno, on what I believed was its last flight. On the way I detoured a little, making a flyby at Lompoc, California where my family was. Upon making the delivery of the F-86A that I had enjoyed flying, I bid her adieu, never dreaming that I would ever lay eyes on her again. It was the last '86A to leave the Ontario Guard. The 196th had transitioned into the F86D, not one of my favorite '86 models.

I transferred to the 115th FIS at Van Nuys. It was closer to my home in Lompoc, plus I got the ultimate thrill of flying the F-86H, the culmination of my 2,000 hours of F-86 time. North American had clearly saved the best for last with the '86H. It was truly a joy to fly.

INTO THE EYE OF THE HURRICANE

by Lon Walter

The two Sabres were right in the eye of the hurricane at 35,000 ft! (How's

that for an opener?) Well, maybe not actually IN the eye, but probably pretty

damn close. How did they get there? Read on.

The place was Eglin AFB, Florida, a huge complex of airfields and test ranges almost the size of Rhode Island. The date was 26 September 1953, and the time was early morning. A major hurricane was heading north, and the eye was about 90 miles south of the main base. At Eglin, the two big test units, Air Proving Ground Command (APGC) and the Air Force Armament Center (AFAC), had sheltered most of their fighters in sturdy hangars and had flown out those aircraft which couldn't be accommodated in hangars. The base was ready.

As a project officer and test pilot in AFAC, I was catching up on my paper work. The two F-86E-1 test beds (50-581 and 50-583) assigned to my project (testing the new K-19 gunsight) were among those hunkered down in the AFAC hangar. Everyone expected to be released before noon to return to their quarters and to ride out the hurricane with their families. A telephone call was about to change all that.

The call was from the base operations officer. He had received a call from the TAC fighter squadron commander whose outfit had been shooting gunnery out of Auxiliary Field #2, about twelve miles from the main base. The squadron commander stated that he didn't have enough qualified pilots to fly all of his F-86s out of Field 2, and could some of the Eglin test pilots come over and help out? I said, "sure", called my wife (She was not terribly happy that I was "bailing out" and leaving her alone with our baby daughter to face the storm's fury.), picked up my flying gear, and drove up to Field 2. There I joined about 12 APGC and AFAC F-86 pilots - apparently most of the TAC squadron pilots were not weather qualified.

As we filed our flight plans to Perrin AFB, TX, the rain was coming down in buckets and the dark clouds were solid from about 500 ft to Lord-knows-where-the-tops-were. The TAC Sabres were almost-new F-86F-30s, and we planned to launch in flights of two. The hurricane clouds were forecast to extend inland almost to Jackson, MS along our flight path. I was to fly wing on Major Lyle King, one of the greatest fighter pilots I ever knew, and a real gentleman. (He died when his F-86D quit on take-off a few years later, and the huge King Hangar at Eglin is named for him.) Neither of us had flown an F-30, but this didn't seem to present any problem.

As we lined up for take-off, I estimated the eye of the hurricane was 70-80 miles to the south and the rain was beating down on us, but we were going to fly northwest (away from the storm). It should have been fairly routine.

On take-off, I tucked in real tight on Lyle King's right wing as we plunged into the murk, and was able to keep him in sight in spite of incredibly thick clouds. He was a smooth and considerate leader, and this helped a lot. As we climbed through dark clouds, rain, and turbulence, I decided it was more important to keep from losing sight of Lyle than to check my instruments, and after we leveled off at 35,000 the flight conditions were, if anything, getting worse - not better. Our only navigation aid, the radio compass, was useless with all the thunderstorm activity (No radar in those days!). At that time, Major King asked me if I could tell him what my gyro compass read. After a quick glance, I replied in a surprised voice that it showed we were heading SOUTH! We were approaching the eye of the storm! Major King said that he had suspected his gyro compass was 180 degrees off, but hadn't been able to confirm it because the turbulence had his standby compass (called a "whiskey" compass - but that's another story) bouncing around so much. "Lon, would you take over the lead and get us out of here?" Gulp! "Rog, I'm going to head northwest until we break out."

We popped out of the clouds somewhere between Mobile, AL, and Jackson, and the rest of the flight to and from Perrin was relatively uneventful. But we were not the only ones who had problems.

Another AFAC test pilot, Bill Snyder, recalls that he and his wingman, Frank Flanagan, took off and immediately lost all of their gyro instruments. They somehow managed to stay beneath the clouds (which Bill says were about 200' a.g.l.), and after some expert low-level flying in miserable weather, they were able to return to Field 2 and land their fully loaded Sabres.

An APGC pilot was climbing out over Crestview, FL (about 30 miles north of Eglin Main), when he, too, lost all of his flight instruments. He bailed out after he found his Sabre in a spin, but his wingman managed to recover and land at Barksdale AFB, LA, with his "g" meter showing +9. Several other flights reported major problems with their airplanes.

I heard later that the squadron

commander had been canned, and that TAC was embarrassed that the beautiful

F-86Fs were in such lousy condition. Additionally, there were some questions

about why the commander waited so long to evacuate his fighters, and why his

own jocks weren't "qualified" to fly them out. All in all, it was

not one of TAC's finest hours!