Aerial photography may

be divided into six categories: vertical, oblique, fan, continuous

strip, panoramic, and aerial cinematography.

A vertical photograph

is an aerial photograph taken with the camera axis vertical, or

as nearly vertical as practicable, in an aircraft. The camera axis,

therefore, is perpendicular to the earth and ground features appear

in perspective and with minimum distortion of their horizontal dimensions.

Vertical photographs

have relatively small errors of scale and azimuth which result from

tilt, variation in relief features, and optical distortion. Measurements

can be accomplished easily and with moderate accuracy. Scale is

fairly constant throughout the photo. Verticals provide excellent

aids to crews accomplishing high altitude missions.

A disadvantage

of vertical photography is that it presents an image which is seen

from an unfamiliar point of view. Also, only a limited field of view

is shown.

Vertical

reconnaissance photography is generally divided into three categories:

spot photography, reconnaissance strip, and mosaic photography.

SPOT PHOTOGRAPHY

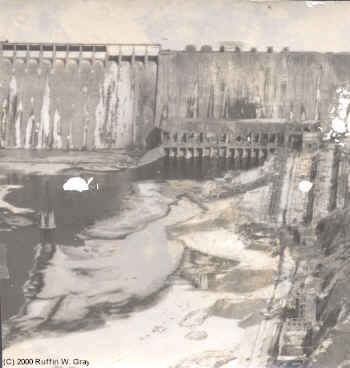

Spot photography

consists of a single photo or stereoscopic pair of a particular

installation; e.g., a photo of an airfield, the objective centered

or pinpointed on the photo.

RECONNAISSANCE STRIP

A reconnaissance

strip is a single flight line of overlapping photos taken at a constant

altitude between two points; e. g., a strip of photos along a rail

line.

MOSAIC PHOTOGRAPHY

Mosaics are two or more

reconnaissance strips, usually parallel, with side lap between strips;

e.g., parallel photo strips over a large city or battle area.

Oblique

Photography

An oblique photo is an

aerial photograph taken with the camera axis directed intentionally

between the horizontal and the vertical. Therefore, the aircraft

does not have to fly directly over the area to be photographed.

A high oblique shows the horizon; a low oblique does not. A high

oblique photo shows much more area than a vertical photo taken with

the same focal length and from the same altitude; however, the images

grow smaller toward the horizon. Objects in the background tend

to lose their proper perspective, proportionate to the obliquity

of camera angle, to the extent that the correct horizontal plane

of individual objects cannot be determined.

In oblique photos, the

terrain appears as a conventional image rather than the map like

presentation of the vertical. Since oblique photos are more pictorial

and more readily read, they provide excellent briefing aids for

crews accomplishing low level missions.

One disadvantage

of oblique photography is that scale diminishes from foreground to

horizon. Calculations are also difficult and must be accomplished

by means of trigonometric computation. Observation is limited to line

of sight. In addition, oblique photography is not very effective at

night.

Oblique

photography is generally divided into three categories: spot photography,

reconnaissance strip, and dicing photography.

SPOT PHOTOGRAPHY

Spot photography

consists of a single photo or stereoscopic pair of a particular installation,

c. g., a photo of an airfield, the objective centered or pinpointed

on the photo.

RECONNAISSANCE STRIP

A reconnaissance

strip is a single flight line of overlapping photos taken at constant

altitude between two points; e. g., an oblique strip along a coast

line, showing beach and coverage inland.

DICING PHOTOGRAPHY

Dicing photography consists

of oblique photos taken from an oblique camera position at extremely

low altitude and high speed; e. g., dicing run of a highway to determine

the number of troops, type of vehicles, and armament of an enemy

army.

Fan

Photography

Fan photography

is obtained from combinations of vertical and oblique camera installations.

Fan photography is used for strip and mosaic coverage because of its

wide lateral coverage along a single flight line. Its disadvantage

is that the scale diminishes from the center to the edge.

Continuous

Strip Photography

The purpose

of the strip camera is to permit taking a continuous aerial picture

of the terrain while the aircraft is flying at low altitudes and at

high groundspeeds. By the proper selection of components, either single

or stereoscopic photographs may be obtained from a single camera for

reconnaissance purposes.

The camera

provides stereoscopic pictures by producing two adjacent strip exposures.

The images, when viewed through a stereoscopic viewer, are three-dimensional

in nature. During World War II, the Navy put the strip camera to considerable

use in the determination of water depths and heights of obstacles

at landing beaches. At present, strip photography is employed at low

altitudes.

The strip camera employs

the moving film principle (film synchronized with image movement)

to obtain continuous aerial strip photography. The movement of the

film across the focal plane behind a variable-width slit is synchronized

with the speed of the aircraft over the ground. Photography at maximum

speed is thereby made possible.

Panoramic

Photography

Panoramic photography

is photography obtained by swinging or "panning" an aerial

camera to photograph the terrain from horizon to horizon. Actually

the camera is not swung. A dove prism is rotated in front of the

camera lens and the result is as though the camera were swung.

Aerial

Cinematography

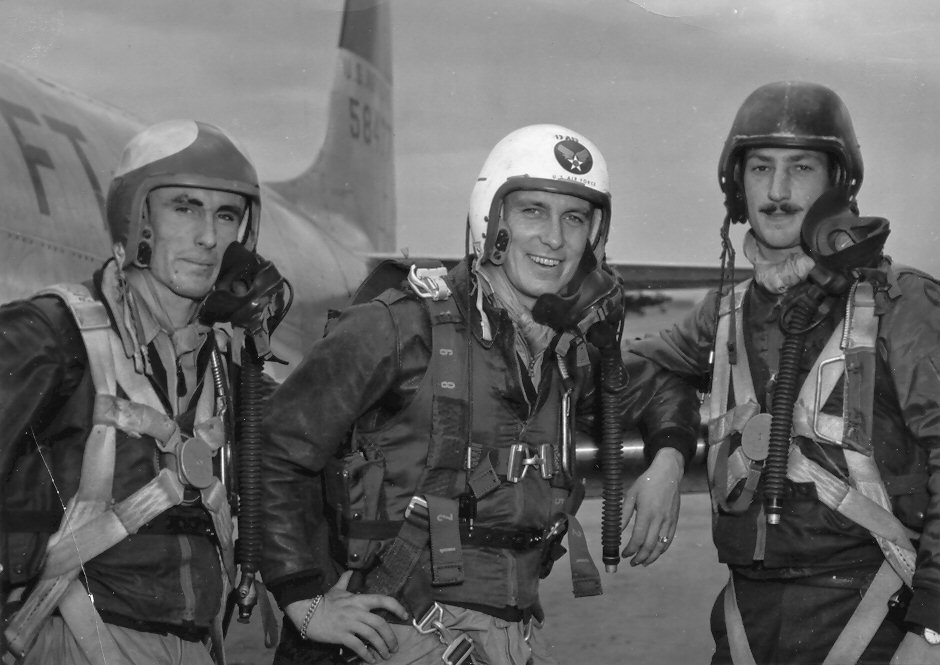

Because the Air Force

started using jet aircraft, a complete change in the techniques

of taking aerial motion pictures had to be made.

When photographing from

a jet, it is necessary to shoot through the Plexiglas which has

very little if any flat surface; therefore, the camera lens must

be placed as close to the glass as possible. The Plexiglas should

be blackened out in all areas surrounding the camera and in the

immediate area of the camera. This must be done to minimize the

reflections. It may be done either by taping a dark cloth or brown

paper inside the canopy or by painting the surface with flat black

poster paint. Poster paint may be easily removed with water at the

completion of the mission.

Another method of minimizing

reflections from Plexiglas is to construct a cone of black cloth

with an elastic in the small end that will fit around the lens housing

and viewfinder, with the wide end taped to the Plexiglas. Care should

be taken that the wide end of the cone allows sufficient width to

accommodate any necessary camera panning and tilting. The rims of

the lenses should also be blackened to prevent their reflection

in the Plexiglas.

When photographing air

to air combat runs on which napalm bombs are being dropped, rockets

are being fired, or strafing is taking place, perfect timing is

essential. The photographer and pilot must work as a perfect team

at all times, and the photographer must be in constant radio contact

with the pilot of both the camera aircraft and the aircraft being

photographed.

AIR TO GROUND

Air to ground missions

normally necessitate using a camera with large film capacity to

cover the longer scenes fully. Because of the unusual degree of

tilt needed and the larger type camera used, an aircraft with more

room for movement is desirable. Normally this type of photography

is performed from a cargo door, waist hatch, bomb bay, or if direct

verticals are necessary, a camera hatch on the floor of the aircraft.

A camera with a variable type shutter is recommended. The shutter

degree opening should be 90 degrees or less when photographing straight

down at lower altitudes; if this is not done, a picket fence type

effect results. Photographing bomb drops and bomb evaluation missions

are classified in this air to ground category.

GROUND TO AIR

Ground to air cinematography

entails many varied assignments for the motion picture cameraman.

A few are: air-to-ground support, test of new type aircraft, guided

missiles, fire power demonstrations, and data recording. The cameraman

must be in constant practice to be proficient in tracking airborne

missiles. Camera speed and shutter speed vary, depending on the

type of coverage desired. A tripod and the down chain should be

used because longer focal length lenses are usually needed which

demand a very sturdy mount. To date, no known professional type

tripod is capable of direct overhead tracking without some type

of modification such as a 90-degree angle placed between the friction

head and the camera body. Filters should be used in this type of

mission due to the atmospheric haze frequently encountered. The

choice of filter depends entirely upon the location of the work

and the desired results.

Aerial cinematography

may be used to great advantage by the Air Force in all categories

listed above, whether it be in data recording for research or on

an air strike. Through motion pictures, the mission of the Air Force

is best told to its own personnel and to the general public.

Photographic,

visual, weather, and electronic reconnaissance are all important in

securing information necessary to wage successful warfare. In this

manual, however, we will be concerned only with aerial photographic

reconnaissance.

We have discussed the

types of aerial photographic reconnaissance and seen how the cycle

from pioneer through strike to surveillance provides a comprehensive

survey of the enemy, his targets, and terrain. Cartographic reconnaissance

provides photography necessary for preparing maps for ground operations

and navigational and target charts.

These aerial

photographic reconnaissance missions are accomplished by various types

of aerial photography: vertical, oblique, fan, continuous strip, and

cinematography.

In this chapter, we have

seen the over-all picture of aerial reconnaissance and more specifically,

aerial photographic reconnaissance.

The material in the next

chapter goes into the principles with which you must be familiar

in performing aerial photographic reconnaissance.